Training and Planning to Drop an Atomic Bomb

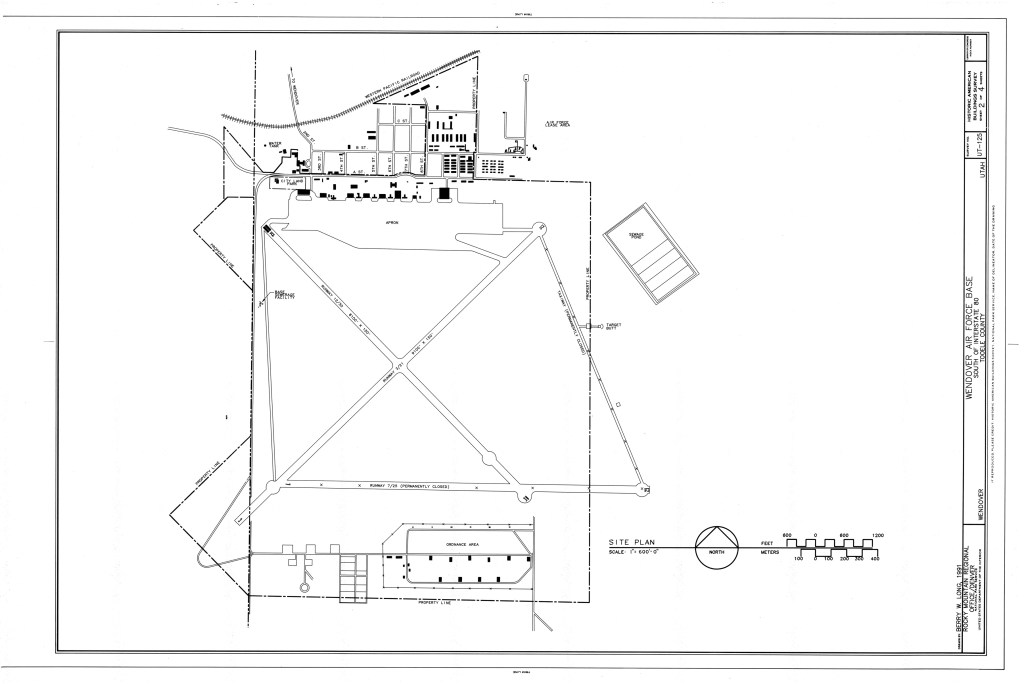

On 17 December 1944, the atomic bombing missions were tasked to Colonel Paul W. Tibbets and his newly formed 509th Composite Group, which would train specifically for the atomic bombings at Wendover Army Airfield, Utah. The unit stationed at Wendover, the 216th Army Air Force Base Unit, would provide a Flight Test Section and a detachment from the Group’s 1st Ordnance Squadron.

To acquire vehicles, equipment, and other materials that were rationed during the war, the Manhattan Engineering District had received a AA-3 priority rating from the War Production Board, which was later upgraded to AA-2X in March 1943. As the facilities at Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos were on the cusp of reaching planned production-level operations, the District was authorized a AA-1 rating, effective 1 July 1944. If the Manhattan Project was in dire need of critical materials, they could also use a AAA priority, the highest such rating, on a limited basis through the Army and Navy Munitions Board. If Colonel Tibbets faced push back from the Army Air Forces, he could invoke the code word “Silverplate,” which would effectively move him to the highest priority for personnel, equipment, and resources. This term, authorized by General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, Chief of Staff of the Army Air Corps, would come to identify the B-29 bombers that were modified to carry Little Boy and Fat Man units. The first modified B-29 was designated an MX-469 or “Pullman” type.

To better maintain the secrecy of their mission, the 509th needed to be a mostly self-sustaining unit, able to draw upon their own men and equipment and eliminating the need to bring in other units or contractors as much as possible. To do this, Colonel Tibbets fleshed out the core of his group, the 393rd Very Heavy Bombardment Squadron, with auxiliary formations. These included the 603rd Air Engineering Squadron and 1027th Air Engineering Squadron of the 390th Air Service Group, the 320th Troop Carrier Squadron, the 1395th Military Police Company (Aviation), and the 1st Special Ordnance Squadron (Aviation). In June 1945, the 509th was topped off with the 1st Technical Detachment, a team of civilian and military technicians, engineers, and scientists tasked directly from the War Department that would be responsible for assembling and handling the bombs. These personnel were organized under Project Alberta, which was disbanded after Japan’s surrender when their part in the war was complete.

Training included flying and operating the modified Silverplate B-29s and conducting missions using five ton dummy bombs, called “Pumpkins,” to simulate the size, weight, and rotund shape of the Fat Man unit. Because there would be only two bombs available for the actual combat mission, the B-29 crews practiced both visual and radar-assisted bombing. Even if there was cloud cover over the target city, the crew would still be able to make out prominent terrain features that would assist in dropping the bomb within an acceptable distance from the aiming point. Conducting a bombing run with only a single strike aircraft meant that there would be no pathfinder aircraft flying ahead to mark the target.

Although hundreds of Pumpkins met their demise on bombing and gunnery ranges in the United States, the 509th Composite Group also conducted several dozen Pumpkin practice missions over Japanese cities before and after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. The 509th Group’s flights over Japan were labelled as “Special Missions,” of which the 13th was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the 16th was the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. The first of these Pumpkin sorties began on 20 July, only a few days after the Trinity Test, while the last six sorties were flown on 14 August 1945, the day that Emperor Hirohito recorded his message of the Japanese acceptance of the provisions laid out in the Potsdam Declaration.

The target list for the Pumpkin missions included Toyama, Fukushima, Kobe, Nagoya, and other Japanese cities subject to conventional bombing. However, no Pumpkin missions were targeted against the cities of Kokura, Hiroshima, Niigata, or Nagasaki. Orders from the highest echelons of the United States military instructed the 20th Air Force to avoid these four cities for a very specific, but also very classified, purpose.

After the success of the Trinity Test in the New Mexican Jornada del Muerto on 16 July 1945, preparations were made for the use of the atomic bombs on targets in Japan. In April, a few months earlier, Manhattan Project Commander Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves had directed the formation of a committee to compile a list of four possible Japanese targets.

At the end of May, the Target Committee proposed the following cities as the highest priority targets: Kokura, Hiroshima, Niigata, and Kyoto. While General Groves approved all of the cities proposed, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson vetoed Kyoto as a target. Although he certainly had his own reasons for his non-negotiable commitment to removing Kyoto from the atomic bombing short list, it was not because of his reminiscing of a pleasant honeymoon spent there. Stimson was undoubtedly aware of Kyoto’s status as one of the most important historical, spiritual, and cultural locations in Japan, second only to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Accordingly, Nagasaki replaced Kyoto as the fourth city only two weeks before the bombs were dropped.