Special Mission 16: The Atomic Bombing of Nagasaki

On 6 August, the Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Tibbets and carrying Little Boy, took off from North Airfield on Tinian. Colonel Tibbets’ primary target was Hiroshima. Kokura and Nagasaki were selected as second and third alternates, respectively. Accompanying the Enola Gay were Major Sweeney’s crew in The Great Artiste, carrying instrumentation to measure the blast effects from the bomb, and Necessary Evil, flown by Captain Marquardt’s crew and assigned to observe and photograph the results of the bombing.

Later that day, President Harry S. Truman announced the results of the first atomic bombing in history.

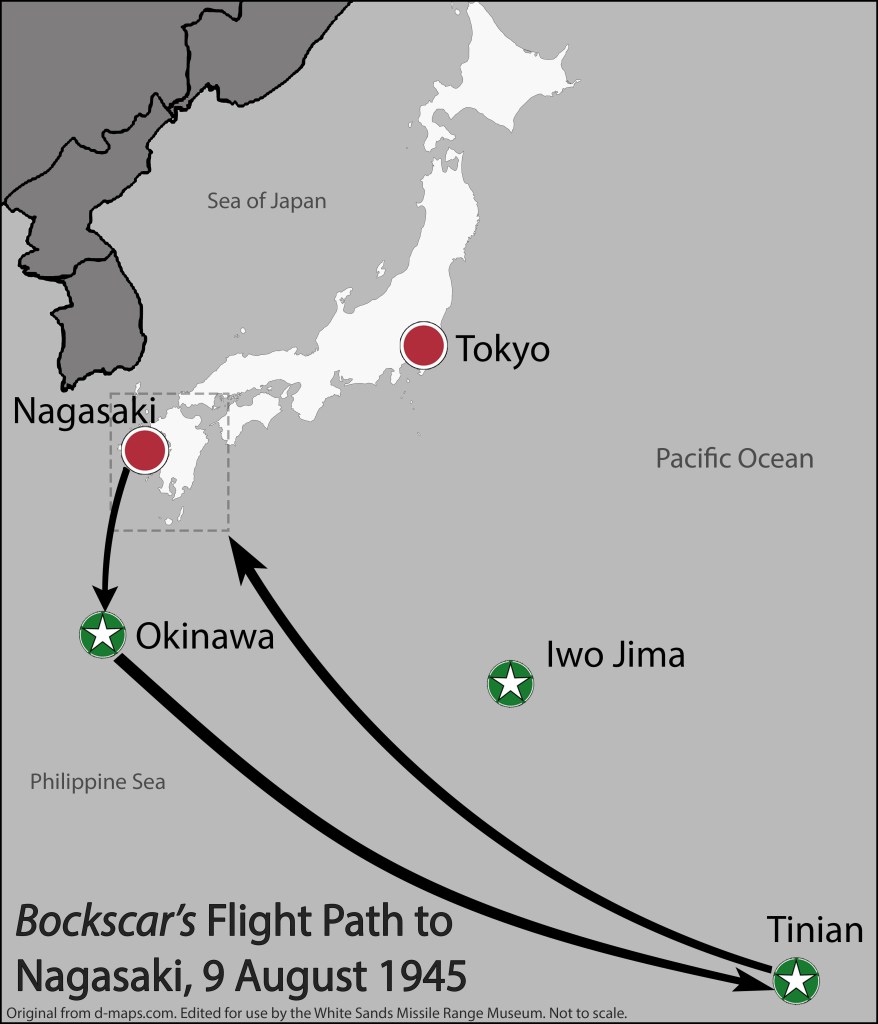

After the successful detonation over Hiroshima and with no response to the United States’ ultimatum calling on Japan to surrender, personnel at Tinian began to prepare Fat Man for the next bombing mission. The next target selected was Kokura with Nagasaki chosen as the secondary. Even though Niigata was on the Target Committee’s list, it was an impractical target for this mission, as the B-29s did not have the range required to safely fly from Tinian to Kokura/Nagasaki to Niigata and then back to Tinian without at least one or two stops for refueling. On 8 August, the crews of the aircraft assigned to the mission conducted a short, one hour flight around Tinian. Fat Man unit F33 was expended during this rehearsal run. Unit F31 was prepared for the Nagasaki mission while F32 remained on standby, waiting for the next core to arrive from the States.

The second bombing was originally scheduled for 11 August. However, incoming weather reports forecast bad weather for almost a week. Military planners had developed the idea of a “one-two knockout punch” using atomic bombs that would force Japan to surrender unconditionally. This idea gained heavy traction after 6 August as the destruction inflicted upon Hiroshima was photographed and damage statistics began to accumulate. In order to maximize the knockout punch, the first atomic bomb had to be followed by a second as soon as possible to give Japan’s leaders the impression that America had a stockpile of atomic weapons, each with a Japanese city’s name on it. Instead of waiting for the storm to pass, the date for the bombing was moved to begin in the early morning on 9 August.

Moving the date up required alterations to the crews executing the mission. The original plan called for The Great Artiste, piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney, Commander of the 393rd Heavy Bombardment Squadron, to carry Fat Man for the bombing on Kokura. Accompanying as support aircraft were Bockscar, piloted by Captain Frederick C. Bock and carrying instrumentation and other measuring equipment, and Big Stink, piloted by Major James I. Hopkins, which would observe and photograph the aftermath of the bombing. Major Hopkins, serving as the unit’s Operations Officer, signed the operations order for the Fat Man mission. Although Big Stink and many other Silverplate aircraft on Tinian only received names and added nose-art after the atomic bombings, these names will be used for simplicity.

Due to the change of plans, however, the ground crews did not have enough time to move the instrumentation and measuring equipment out of The Great Artiste and into Bockscar. Instead, the two aircrews would swap aircraft. Captain Bock’s crew (C-13) would now fly The Great Artiste and operate the instrumentation. Major Sweeney’s crew (C-15) would fly Bockscar and drop Fat Man on Kokura. It was a common occurrence for crews of the 393rd to fly missions in other bombers in the unit. It was also common for commanders and staff officers, such as Colonel Tibbets and Major Sweeney, to be inserted into crews as mission commanders. In the case of C-15, the regular crew commander, First Lieutenant Charles D. Albury, would be moved to co-pilot. C-15’s usual co-pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Frederick J. Olivi, would become third pilot.

| Commander | Major Charles W. Sweeney |

| Co-pilot | 1st Lieutenant Charles D. Albury |

| Assistant Co-pilot | 2nd Lieutenant Frederick J. Olivi |

| Weapons Commander | Commander Frederick L. Ashworth |

| Assistant Weaponeer | Lieutenant Philip M. Barnes |

| Bombardier | Captain Kermit K. Beahan |

| Navigator | Captain James F. Van Pelt Jr. |

| Flight Engineer | Master Sergeant John D. Kuharek |

| Assistant Flight Engineer | Staff Sergeant Raymond C. Gallagher |

| Electronic Countermeasures Officer | 1st Lieutenant Jacob Beser |

| Radar Operator | Staff Sergeant Edward K. Buckley |

| Radio Operator | Sergeant Abe M. Spitzer |

| Tail Gunner | Sergeant Albert T. DeHart |

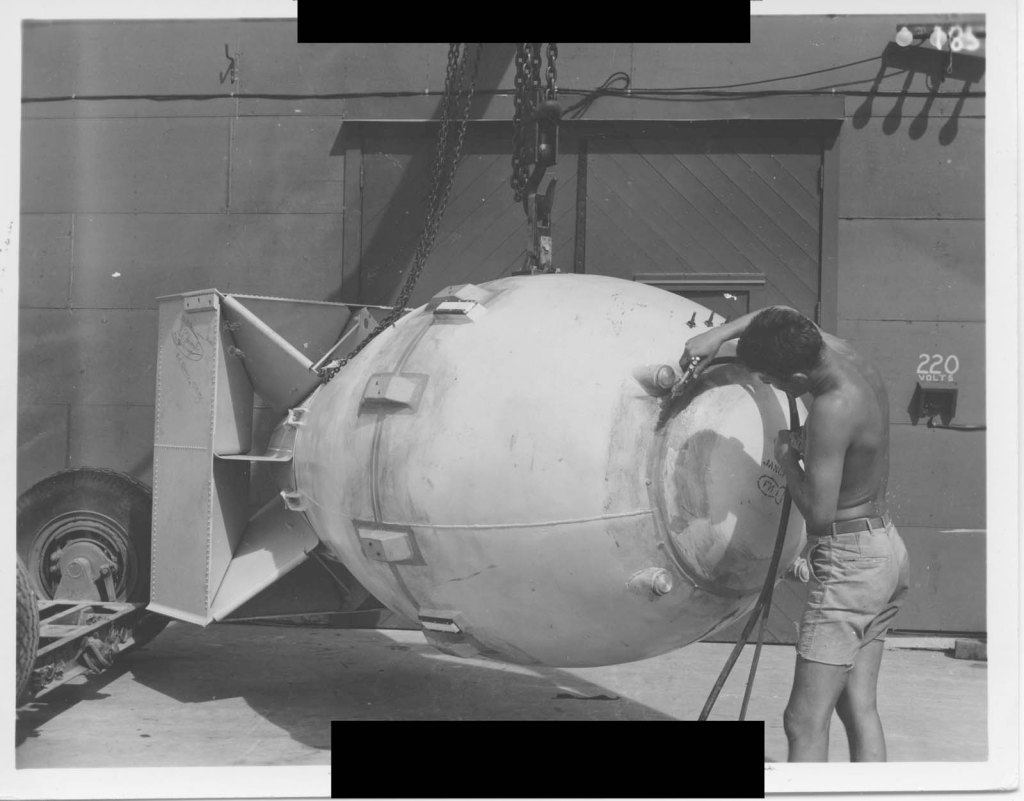

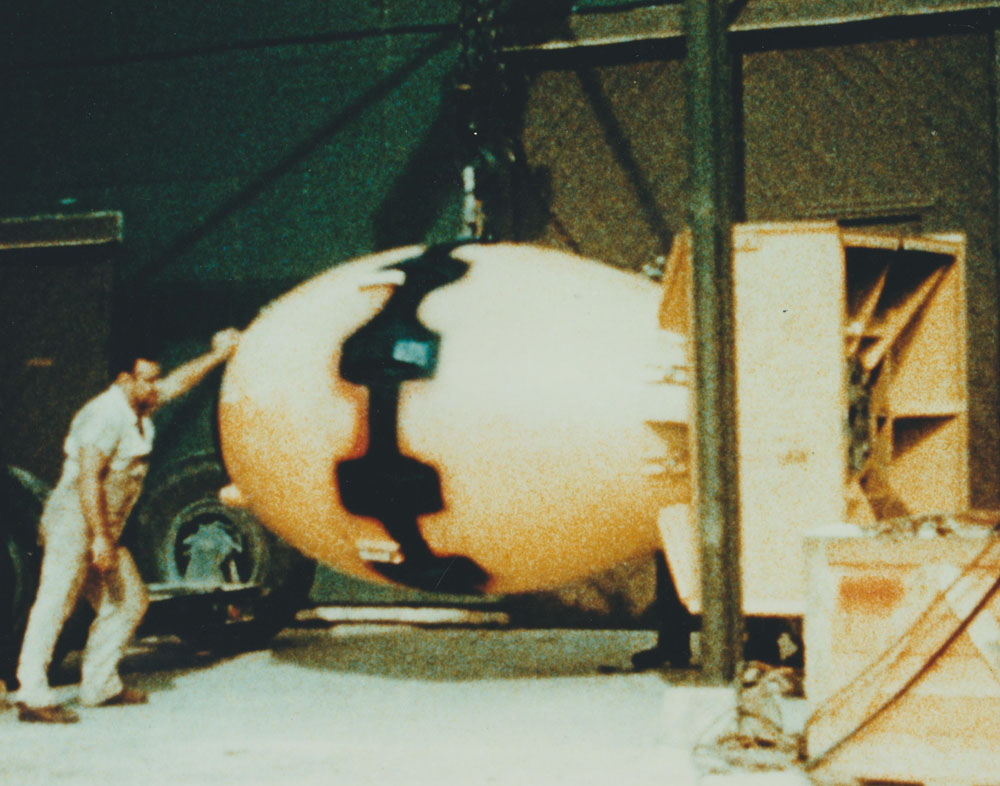

Video of the final preparations show workers applying adhesive strips and several layers of spray-on sealant to the bulbous shell, which emerged from Assembly Building #2 already yellow in color, which came from a painted-on layer of zinc chromate, a carcinogenic salt compound commonly used as a corrosion-resistant primer on metal surfaces. For the finishing touch, Dr. Norman F. Ramsey added his signature to the nose cap alongside other Manhattan Project and Project Alberta personnel and a stencil of Fat Man’s outline labelled “FM.” Just above the stencil was the acronym “JANCFU,” short for “Joint Army-Navy-Combined/Civilian ‘Fouled’ Up” (this being a polite translation). Whether this was simply a succinct observational commentary of how well the mission was going so far or an attempt to ward off bad luck, there is no way the ground crews could have known just how prophetic the stenciled acronym was going to be.

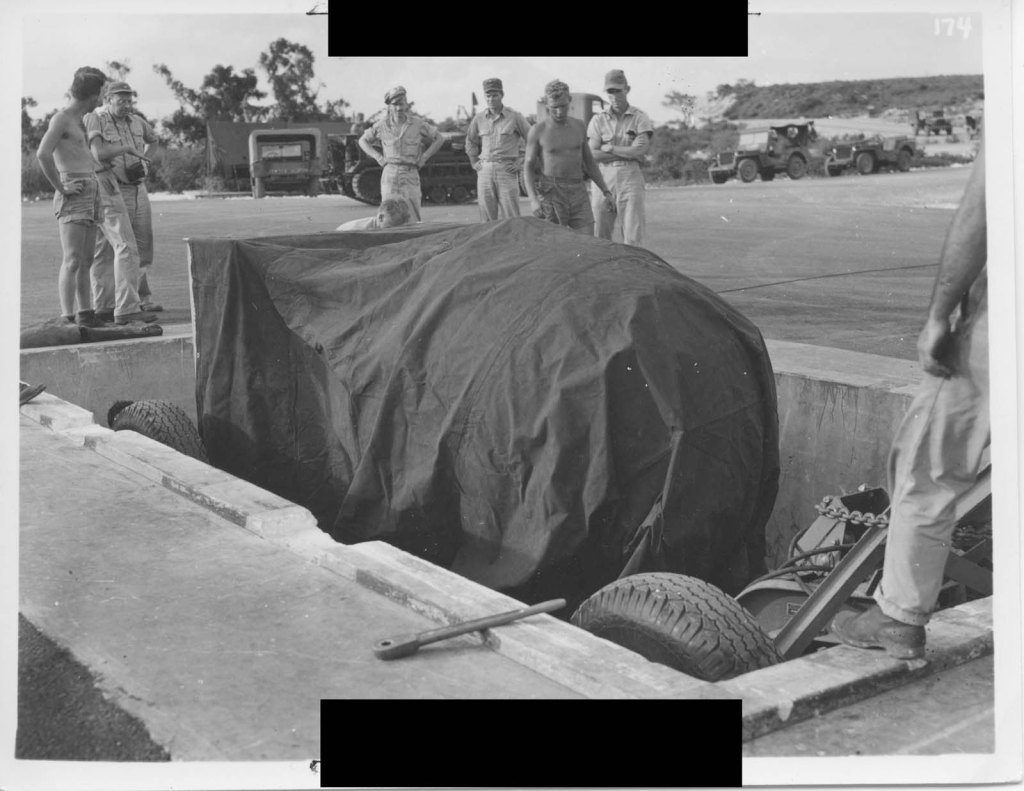

The truck and Fat Man made their way down to the loading pit in a convoy. Although an attack on the atomic bomb was highly unlikely, the Project Alberta personnel were not going to risk anything bad happening so close to Fat Man’s final delivery. Even though Tinian had been cleared of the last of the Japanese garrison, there was always the fear that a lone Japanese soldier, armed with a samurai sword or rifle with bayonet, could burst through the foliage when the Americans least expected it. Near the northern end of the island, crewmen detached the trailer and pushed it by hand to the loading pit. As the loading personnel worked, Military Policemen stood guard around the site with black “MP” bands on their sleeves and M3 “Grease guns” slung over their backs.

Preparing the Fat Man unit for the upcoming mission was not as simple as loading up and taking off. Fat Man and Little Boy’s size and weight necessitated the construction of a loading pit with a lift that was capable of rotating, lowering, and then raising the bomb to secure it in the modified bomb bay. The two loading pits are still intact and viewable on Tinian today: Bomb Pit #1 was used to load Little Boy into the Enola Gay and Bomb Pit #2 was used to load Fat Man.

The mission briefing began at thirty minutes after midnight on 9 August. The contents of the briefing were similar to those of three days prior for the Hiroshima mission and included weather reports, reconnaissance photos of the target cities, and bailout contingencies. Major Sweeney and his crew were given specific instructions for the mission. First, that the three strike aircraft, Bockscar, The Great Artiste, and Big Stink would maintain radio silence. With the release of President Truman’s announcement regarding Hiroshima, Japanese intelligence would be expecting another atomic bomb in the near future. If the Japanese could plot Bockscar’s location, speed, and direction by using their radio traffic, the remainder of the Japanese air forces could send interceptors with enough lead time to get to the B-29’s altitude and attempt to engage them. Second, that they should proceed to the target no later than fifteen minutes after the rendezvous at Yakushima Island. And third, the bombing run needed to be visual; even with training on radar bombing runs, Colonel Tibbets wanted to ensure that they knew exactly where Fat Man was dropped on the target city. Because the weather reports over mainland Japan looked clear, this would not pose much of a problem anyway.

After the briefing, flight and ground crews began their pre-flight checklists while floodlights surrounding Bockscar illuminated the aircraft. Flight engineer Master Sergeant John D. Kuharek found that one of the pumps for a reserve fuel tank was not operating normally. An auxiliary pump could be used to transfer fuel, but he could only use it sparingly and for a short time. Overworking the pump could break or damage the motor. Although they would still be able to reach Kokura, the crew would almost certainly need to stop at the airfields on Iwo Jima or Okinawa to refuel before returning to Tinian.

This type of problem would ground a bomber for normal missions. However, this was, as the name implies, not a normal mission. Major Sweeney deplaned his crew and walked over to Colonel Tibbets and two of the Joint Chiefs of Tinian (General Farrell, Admiral Purnell, and Captain Parsons) to discuss the situation. Colonel Tibbets’ mission on 6 August had been a picture-perfect “milk run” and he had not even touched the 640 gallons of fuel in the reserve tanks. The fuel was still needed in order to balance out Bockscar’s center of gravity for takeoff and landing, but it would essentially be dead weight that they would have to carry to Japan and back. With the weather on Tinian degrading by the minute, General Farrell reluctantly accepted the risk and Sweeney was given the go-ahead to proceed with the mission as planned.

Most post-war historiography on the Nagasaki mission would state that the auxiliary pump was non-functional and that all 640 gallons of fuel in the reserve tanks was inaccessible. However, this may not be entirely accurate. According to John Coster-Mullen in a speech given in 2005:

“Sweeney flew Bockscar with Kuharek as flight engineer during drops of Fat Man test units on August 1st, 5th, and 8th. Bockscar maintenance records dated 1 August state, ‘Check bomb bay hook-up, have to use upper tank switch to get fuel out of lower tank.’

The post-mission maintenance report dated on the 9th states, ‘Check bomb bay tank hook-up. Lower tank works erratic, appears that booster pump is at fault.’ Tibbets told me that he and Dutch Van Kirk went to see Kuharek in 1995 at the 509th reunion… He said, ‘If I hadn’t been able to transfer that fuel, I wouldn’t be here talking to you, we’d have gone in the water. Sweeney didn’t listen to me! What I told Sweeney was I couldn’t transfer it at normal rate, I had to milk it out a little bit at a time. I was afraid of burning out the pump.’”

Bockscar took off from Tinian at approximately 0347 with thirteen crewmen and one Fat Man on board. Fully aware that their plane was overloaded, Major Sweeney used all of Runway Able to pick up enough speed to get airborne. As Bockscar’s wheels lifted off the ground, they passed right over the remains of B-29s that were unable to gain sufficient speed and had instead crash-glided into the ocean. Sergeant Abe Spitzer knew full well that those planes had been carrying less weight than Bockscar. He also knew that it was rare for bodies to be recovered intact from those crashes. Sighs of relief came only after they were comfortably airborne. As he looked up, he saw the apparition of an angelic figure who helped them survive their white-knuckled lift off. Staff Sergeant Gallagher commented that their angel looked like Lana Turner.

Two minutes later, Captain Bock in The Great Artiste rolled down Runway Baker and took off into the dark morning. In addition to his crew of nine and their instruments to measure the bomb, they were carrying three Project Alberta personnel and one science correspondent from the New York Times. It is likely that neither Captain Bock nor Major Sweeney noticed the last strike aircraft, Big Stink, piloted by Major James I. Hopkins Jr., was delayed in taking off behind The Great Artiste as scheduled. A few minutes late, Big Stink left Runway Charlie with its crew of ten and accompanied by two observers from the United Kingdom, Royal Air Force Group Captain G. Leonard Cheshire, VC, and Sir William G. Penney from the British atomic bomb effort, called the “Tube Alloys” program.

The delay was caused by one of the civilians assigned as an observer aboard Big Stink who had been issued two life rafts instead of a life raft and a parachute. Major Hopkins, already behind schedule, could not afford to wait for him to walk the mile back to the main cantonment and draw a parachute from supply, as required for all personnel aboard the B-29 according to Army Air Corps regulations. The observer was ordered off the plane and could only watch from Big Stink’s prop wash as the photography plane took off in pursuit of the two other bombers. After his plane disappeared into the darkness, the grounded observer began his lonely walk back to the 509th Group’s buildings.

Naval Commander Frederick L. Ashworth, serving as Bockscar‘s weapons commander, wrote a narrative summarizing the events of the first leg of Nagasaki mission:

“The night of our take-off was one of tropical rain squalls, and flashes of lightning stabbed into the darkness with disconcerting regularity. The weather forecast told us of storms all the way from the Marianas to the Empire. Our rendezvous was to be off the southeast coast of Kyushu, some 1,500 miles away. There we were to join with our two companion observation B-29’s that took off a few minutes behind us. Skillful piloting and expert navigation brought us to the rendezvous without incident.”

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Barnes, the assistant weaponeer aboard Bockscar, was getting ready for his regular checks on Fat Man’s circuits and electronic instruments. As he went through the motions, a white indicator light on his electronics panel began to blink rapidly, letting him know that the bomb was primed and only needed a signal from the fusing circuit to detonate. After notifying Commander Ashworth, the two weaponeers pulled out wiring schematics and began to chase down the problem, their work timed by the rhythmic flashes of light. They determined that the problem was caused by incorrectly set switches. Once the switches were reset, the light continued blinking at a slow pace and the two men sighed in relief. Fat Man, looking “clean and smooth and smug,” according to Sergeant Spitzer, settled back down, still hanging from its shackle and swaying slightly with Bockscar as the B-29 continued to navigate the ongoing storm.

The weather reports from the reconnaissance aircraft were supposed to come in sometime after 0700 hours, letting Major Sweeney know which target to head to after the planned rendezvous at Yakushima Island. Sergeant Spitzer, the crew’s radio operator, strained to hear the report through his headset for an hour and a half. The entire time, he could only hear Japanese radio jamming efforts, the droning of the B-29’s four engines, and the usual omnipresent static. Finally, he heard a faint and garbled voice coming in. Shouting for quiet, he missed the first two messages but caught the third: the weather over Kokura was good, 3/10 cloud coverage with some haze. This was followed by another message: Nagasaki was good as well. After Yakushima, they would proceed to the primary target.

| Navy Commander Frederick L. Ashworth wrote the following in his flight log: | |

|---|---|

| 0347 | Take off |

| 0400 | Changed green plugs to red prior to pressurizing |

| 0500 | Charged detonator condensers to test leakage. Satisfactory. |

| 0900 | Arrived rendezvous point at Yakashima [sic] and circled awaiting accompanying aircraft. |

| 0920 | One B-29 sighted and joined in formation. |

| 0950 | Departed from Yakashima [sic] proceeding to primary target Kokura having failed to rendezvous with second B-29. The weather reports received by radio indicated good weather at Kokura (3/10 low clouds, no intermediate or high clouds, and forecast of improving condition). The weather reports for Nagasaki were good but increasing cloudiness was forecast. For this reason the primary target was selected. |

| 1044 | Arrived initial point and started bombing runs on target. Target was obscured by heavy ground haze and smoke. Two additional runs were made hoping that the target might be picked up after closer observations. However, at no time was the aiming point seen. It was then decided to proceed to Nagasaki after approximately 45 minutes spend in target area. |

| 1150 | Arrived in Nagasaki target area. Approach to target was entirely by radar. At 1150 the bomb was dropped after a 20 second visual bombing run. The bomb functioned normally in all respects. |

| 1205 | Departed for Okinawa after having circled smoke column. Lack of available gasoline caused by an inoperative bomb bay tank booster pump forced decision to land at Okinawa before returning to Tinian. |

| 1351 | Landed at Yonton Field, Okinawa. |

| 1706 | Departed Okinawa for Tinian. |

| 2245 | Landed at Tinian. |

Upon reaching Yakushima Island around 0900 hours, Bockscar planned to rendezvous with the other B-29s supporting the operation. They found The Great Artiste, flown by Captain Bock, but continued to circle while looking for Big Stink, flown by Major Hopkins. Unknown to Major Sweeney and Captain Bock, Major Hopkins was circling Big Stink more than a mile above them, wondering where the other two were and whether to proceed to Kokura on the chance that he would see them above the target or head back to Tinian. Unlike Major Sweeney, Major Hopkins had plenty of fuel and continued to run fifty-mile doglegs over Yakushima instead of heading to the rendezvous point above the southwest part of the island.

What Major Hopkins did not initially know while en route to Yakushima was that his entire crew and aircraft had become non-factors in the mission before they had even left the ground; their primary purpose as the photography plane was to obtain photographs of the detonation using the complicated Fastax camera, and the only person on the mission who could operate it, Dr. Robert Serber, was the civilian who had been left on the runway for not having a parachute. The Fastax was the same kind of high-speed camera used to photograph the Trinity Test and was capable of running thousands of frames per second. Its speed was also a limiting factor. It could only carry a few seconds-worth of film in fifty-foot or one hundred-foot reels.

As part of his preparation for the mission, Dr. Serber had worked out what direction to have the Fastax pointing during the planned breakaway maneuver, how long he had to wait after the bomb was dropped to start filming, and how to set and adjust the camera motor’s speed using a rheostat. When he showed up at the 509th Group’s radio shack around half an hour after the strike aircraft had left, a frustrated Colonel Tibbets and General Farrell decided to break radio silence to reprimand the Operations Officer and have Dr. Serber try to explain how to use the Fastax over the radio. Still observing radio silence, Bockscar and The Great Artiste could only listen in to the rebuke followed by Dr. Serber’s attempt to convey technical operating instructions for the Fastax.

Thoroughly chastened, Major Hopkins continued to fly above Yakushima at the wrong altitude, looking for the other B-29s. Group Captain G. Leonard Cheshire, VC, one of the two British observers on the mission, described the situation from his point of view to Major Sweeney years later. Major Hopkins had invited the Group Captain to move from the rear compartment up to the front. Because this required crawling through the tunnel that connected the pressurized compartments, he had taken off his parachute, which was against Air Corps regulations. After reaching the front compartment, Major Hopkins noticed that his guest was not wearing his parachute. Still smarting from Colonel Tibbets’ radio-broadcasted rebuke, Major Hopkins had given the Group Captain a dressing down of his own. Group Captain Cheshire could see the altimeter reading on the flight engineer’s instrument panel and knew that the rendezvous was supposed to be at 30,000 feet (9,144 meters). However, the Group Captain, ever the British gentleman, did not think it was his place to criticize the major’s piloting after the confrontation about his parachute.

With neither of the other planes in sight and with the minutes continuing to slowly tick by, Major Hopkins eventually radioed a question back to base on Tinian, “Is Bockscar down?” Since it was sent in code, the question has also been translated as “Has 77 [Bockscar’s designation] aborted?” According to Commander Ashworth’s recollection after the war, the radar operators on Tinian (as well as Okinawa and Iwo Jima) only heard part of the coded message: either “Bockscar down,” or “77 aborted.” Regardless of the exact translation, the message received on Tinian was decidedly unambiguous: for reasons unknown, the bombing mission was a failure. However, the status of Bockscar and Fat Man was unclear.

Back on Tinian, General Farrell was eating breakfast in the Dog Patch Inn, likely stewing over the events of the previous night and earlier that morning. A mental tally would have noted the following: (a) he had personally accepted the risk of sending Fat Man in a plane that should have been grounded, (b) he and Tibbets had to send that plane through a storm front to get to Japan, (c) Dr. Serber had been left on Tinian, (d) they had to break radio silence, and (e) it was not even noon yet. An aide came in to deliver Major Hopkins’ message. Upon learning that Bockscar had aborted the mission, General Farrell ran out and “tossed his cookies.” Bockscar would not return to Tinian for another twelve hours.

After loitering over the rendezvous point for forty-five minutes, thirty minutes longer than they should have, according to Colonel Tibbets’ instructions, Bockscar and The Great Artiste headed north over Kyushu to the primary target city. Due to heavy cloud and smoke cover from nearby Yahata, the bombardier, Captain Beahan, was unable to locate the designated aiming point. Around them, black puffs of smoke were popping from the many anti-aircraft batteries stationed around Yahata and Kokura, seeming to get closer and closer the longer Bockscar stayed over the target. To throw off the flak gunners, Major Sweeney tried changing altitude, bobbing up and down between bombing runs while their 5-ton payload continued to bump against its sway braces. Circling around, they tried a second bombing run from a different angle. Still, clouds and smoke covered the target area. After three runs, Major Sweeney made the decision break away from Kokura. Master Sergeant Kuharek, his eyes still firmly fixed on the fuel gauges, reported to the pilots that their fuel issue had gone from bad to worse.

Commander Ashworth, very much aware of the strict order to only bomb visually, was willing to try Nagasaki. After all, the weather plane had called in Nagasaki as mostly clear. But the sky over Kokura was supposed to be clear as well. Calling off the mission would mean needing to wait for a week for the incoming inclement weather to pass. As the weapons commander, he held the authority to decide on whether to drop the bomb on a target, ditch it in the ocean, or carry it back with them. Unfortunately for Commander Ashworth, the situation that he was facing required complete deviation from the plan, so much so that none of the mission’s pre-planned radio codes could adequately describe their situation and courses of action. Had it been a more light-hearted moment, he may have thought to send “JANCFU” back to Tinian in place of a situation report.

Master Sergeant Kuharek reported on the fuel gauges; they only had 1,500 gallons (5,678 liters) of fuel left, not even enough to get them back to the emergency landing field at Iwo Jima. Bockscar might run out of fuel and they would have to ditch anyway. With all of this and more on his mind and knowing the importance of carrying out a second successful atomic bombing as soon as possible after the first, Commander Ashworth changed course and authorized a radar-guided bombing run if there was cloud cover over Nagasaki. They would not try to carry Fat Man with them to Okinawa. However, they could only risk a single bombing run.

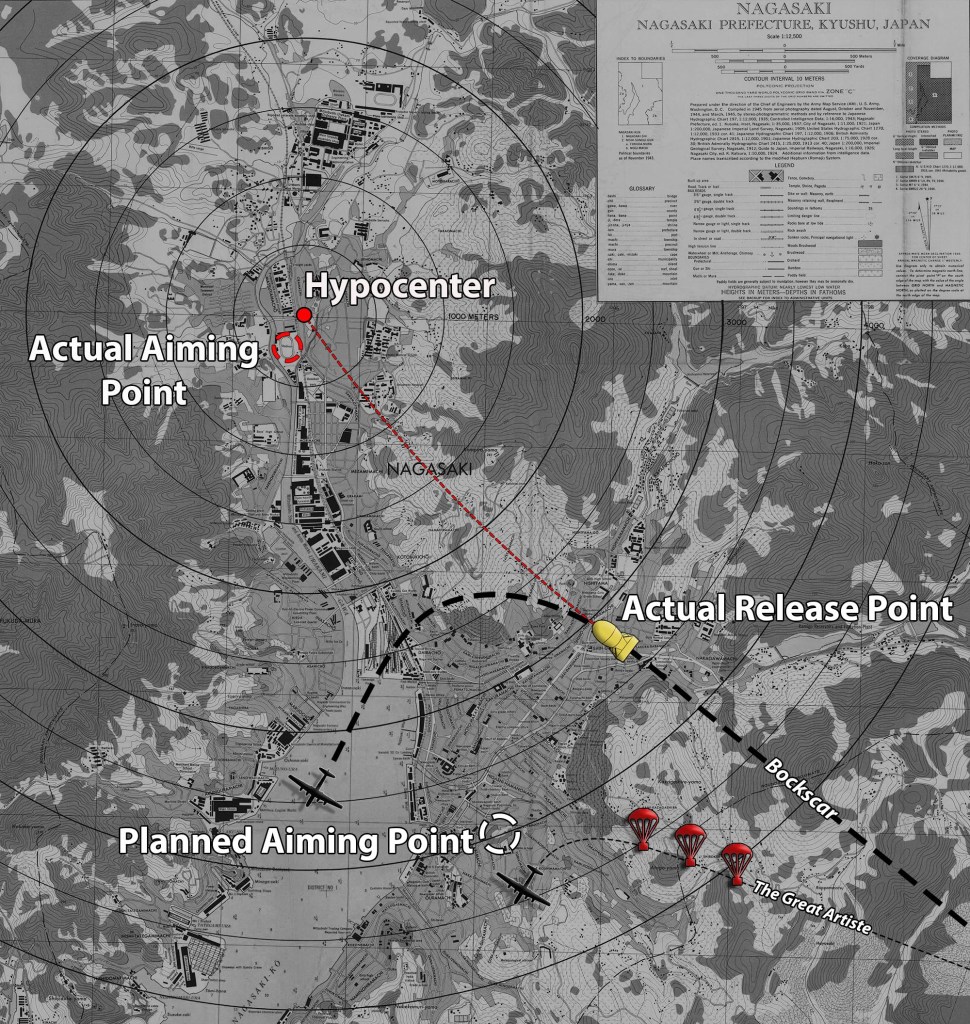

They flew southwest to Nagasaki, almost exactly one hundred miles away if flying in a straight line and reported as being partially covered, only to find the aiming point concealed by clouds as well. At the last minute and with mounting concerns about critically low fuel, there was a break in the cloud cover over the target. Major Sweeney handed over the controls to Captain Beahan, who worked with Staff Sergeant Buckley on the radar set and Captain Van Pelt on navigation, to narrow the guidelines in his sights. They had already flown over the assigned aiming point, located in the heart of the city east of Nagasaki Harbor. Instead, Captain Beahan aimed for a stadium racetrack located along the Urakami River and in between the two Mitsubishi plants. Once aligned, Captain Beahan pressed the release and their five ton payload dropped through the open bomb bay doors. Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki just after 11:01am local Japanese time from an altitude of around 29,000 feet (8,840 meters). It exploded approximately 47 seconds later at an altitude of around 1,650 feet (500 meters) above sea level.

“The bomb burst with a blinding flash and a huge column of black smoke swirled up toward us. Out of this column of smoke there boiled a great swirling mushroom of gray smoke, luminous with red, flashing flame, that reached to 40,000 feet in less than 8 minutes. Below through the clouds, we could see the pall of black smoke ringed with fire that covered what had been the industrial area of Nagasaki.”

Commander Frederick L. Ashworth, Weapons Commander Aboard Bockscar, US Navy.

As soon as Fat Man dropped through the open bomb bay doors, Major Sweeney tried to get Bockscar as far away from the bomb as possible, banking hard to the left in a maneuver that all crews of the 509th Group were taught during the training phase of their operations. Although he had instructed the crew to put their goggles on before the drop, Major Sweeney kept his off; he knew from the Hiroshima mission that they obscured his view of the instrument panels, which he would need to assist him in his hurried getaway. As in the Hiroshima mission, the detonation caused a silent cacophony of lights that illuminated the aircraft’s interior. As the mushroom cloud began to lift above Nagasaki, the B-29 crews felt multiple blast waves hit their aircraft as they rippled through the atmosphere. Below them, the base of the mushroom cloud roiled over Nagasaki’s Urakami Valley.

Flying south-southwest, and with the mushroom cloud still looming large behind them, Major Sweeney had Sergeant Spitzer radio back to Iwo Jima (who would forward the message to Tinian, on to Hawaii, to California, and, eventually, to President Truman) to report the success of the mission:

“Nagasaki bombed visually through 7/10 cloud with good results. No fighter opposition and no flak. High order of detonation. Bombs away time probably 090158Z.”

From his own observations and after conferring with others on board, Commander Ashworth determined that Fat Man had a yield similar to that of Little Boy. However, the crew did notice that the flash of the explosion was brighter, the mushroom cloud rose faster, and the shock waves were stronger than what they experienced on 6 August when the crew had been carrying instrumentation equipment on The Great Artiste for the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

After allowing one fly-by for observation and taking measurements, Major Sweeney began flying south towards the island of Okinawa with a scant 300 gallons (1,135 liters) of fuel left. As they made their approach to the Yonton Airfield (also known as the Yomiton Auxiliary Airfield) near Kadena, they were unable to reach air traffic control on the radio to request clearance to land. Instead, as one of their four engines sputtered out from lack of fuel, Major Sweeney directed Lieutenant Olivi to pop flares, signaling an emergency onboard the aircraft, and made for the runway. With a second engine failing from lack of fuel, the two pilots were unable to fully leverage their reversible propellers to slow down. To make matters worse, the runway on Okinawa was shorter than those on Tinian, as it had been constructed with B-24 Liberators, not B-29 Superfortresses, in mind.

Bockscar, pulling to the left due to the unequal power caused by engine loss, came to a screeching halt near the end of the runway at approximately 1:51pm. Major Sweeney then taxied Bockscar behind a crash cart and came to a halt just in time for a third engine to start sputtering from lack of fuel. When Master Sergeant Kuharek and Staff Sergeant Gallagher checked the remaining fuel levels, they found that they had landed with less than ten gallons remaining out of the 7,250 gallons (minus the fuel still in the semi-operable fuel tank) they originally took off with.

Once they were parked on terra firma, the exhausted crew de-planed and Major Sweeney instructed his men to not say anything about who they were, where they were from, what they were doing, or why they had landed in a controlled crash after launching every signal flare aboard the plane. The crew made their way to the mess hall and were served the finest leftover spam sandwiches that the Army could provide. Meanwhile, Commander Ashworth and Major Sweeney acquired a jeep and made for the communications center in order to send up a follow-up report to Tinian. There, they met Lieutenant General James H. Doolittle, Commander, Eighth Air Force, who authorized them use of his communications center to radio back to Tinian.

Following their meeting with General Doolittle, Commander Ashworth sent the following message back to General Ferrell:

“This message for Farrell (Top Secret). Sweeney, Hopkins and Bock landing Okinawa 090345Z. Arrived rendezvous point at scheduled time waiting about forty minutes being joined by aircraft piloted by Bock only. Received weather reports and made decision to attack primary target. Arrived in target area 090055Z. Target about 3/10 cloud with some haze and heavy smoke. After fifty minutes decided to attack secondary. Attacked in accordance strike report already submitted. Approach made by radar with about last thirty seconds visual. Preliminary conference with observers with Hopkins and Bock places impact approximately on Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, target number 546. Consensus of opinion visual effect equal to or probably greater than at Hiroshima. Column of smoke mushroom reached about 30,000 feet in 3 minutes and soon reached at least 40,000. Dust covered area at least two miles in diameter. Probably fair amount of blast on unprofitable areas. Gasoline consumption at high altitude, cruising, failure to rendezvous, and time over primary target forced decision to drop rather than attempt questionable chance of reaching Okinawa with unit.”

Once their plane was refueled, the crew boarded and made for Tinian. The flight was entirely uneventful and Bockscar landed at 2339 hours. Following their debrief with the intelligence officer, the crew broke into groups and went to celebrate the mission’s success. Around 0500 hours, Major Sweeney arrived at his quarters to find that two officers had acquired General Farrell’s jeep and drove it through his bunk hut. With the events of the day behind him, Major Sweeney made for his bed. He could deal with the jeep problem in the morning.