Damage From the Blast

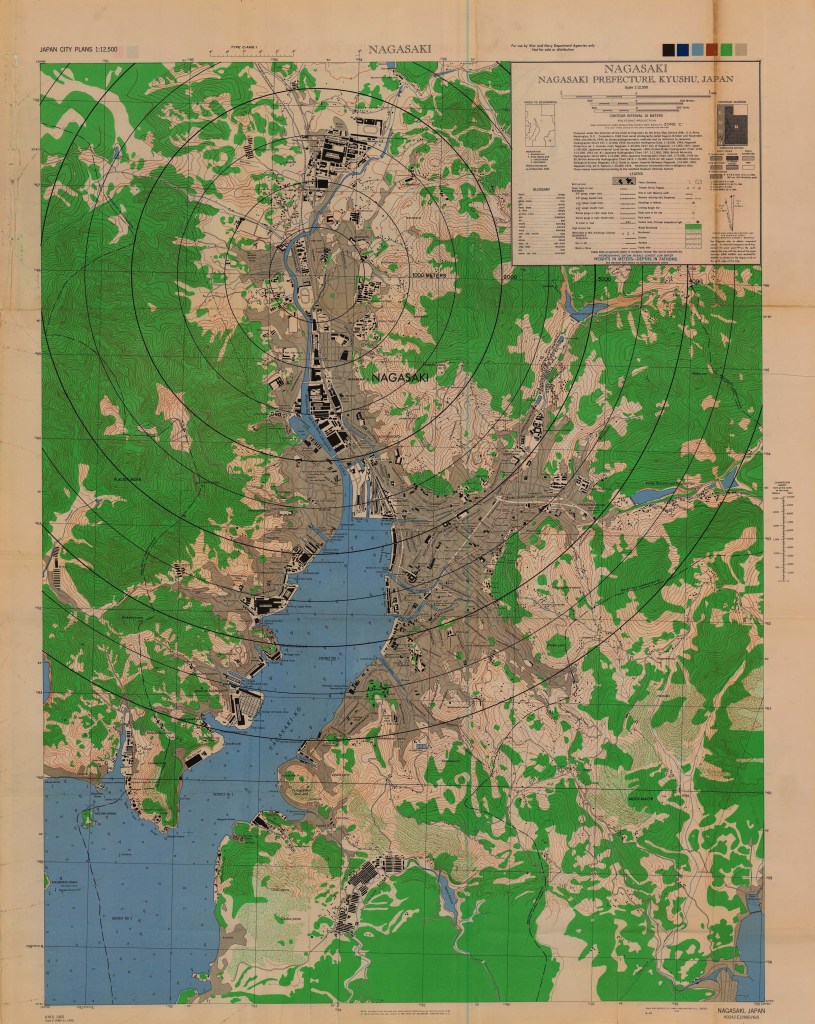

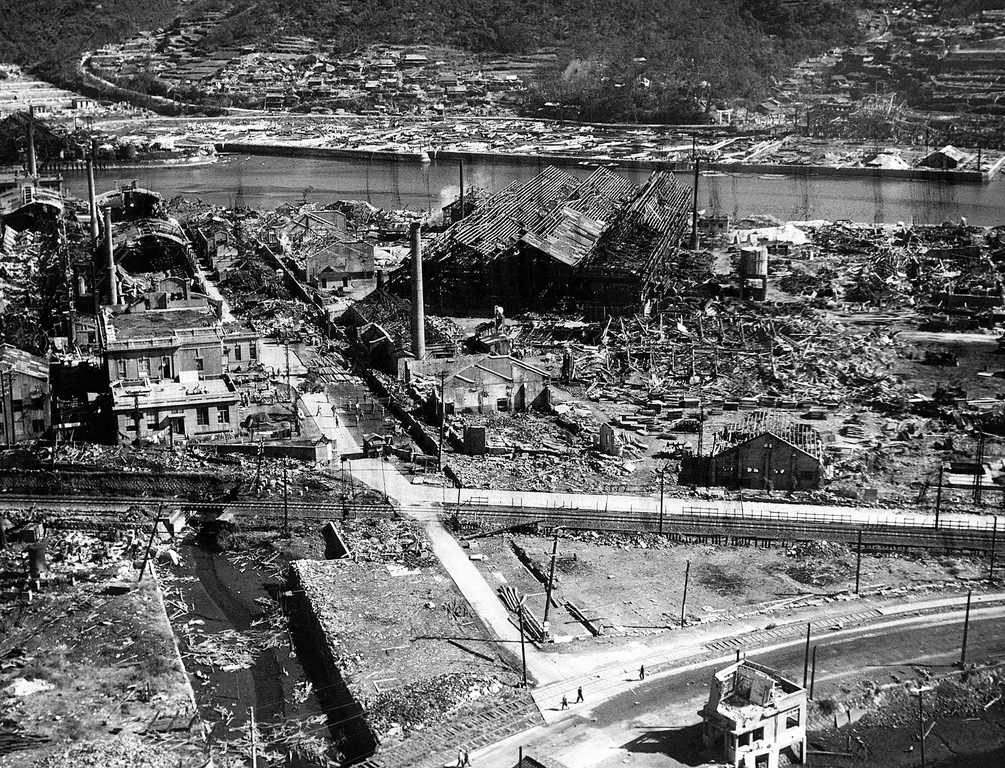

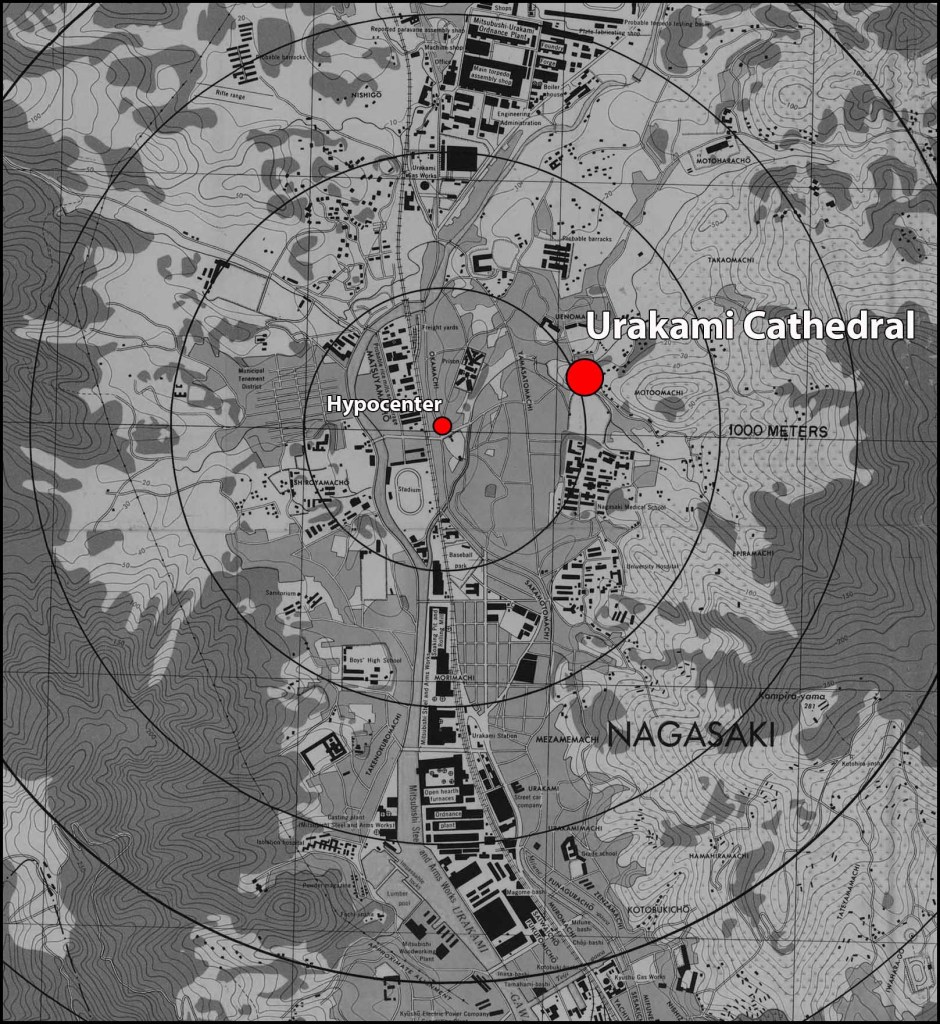

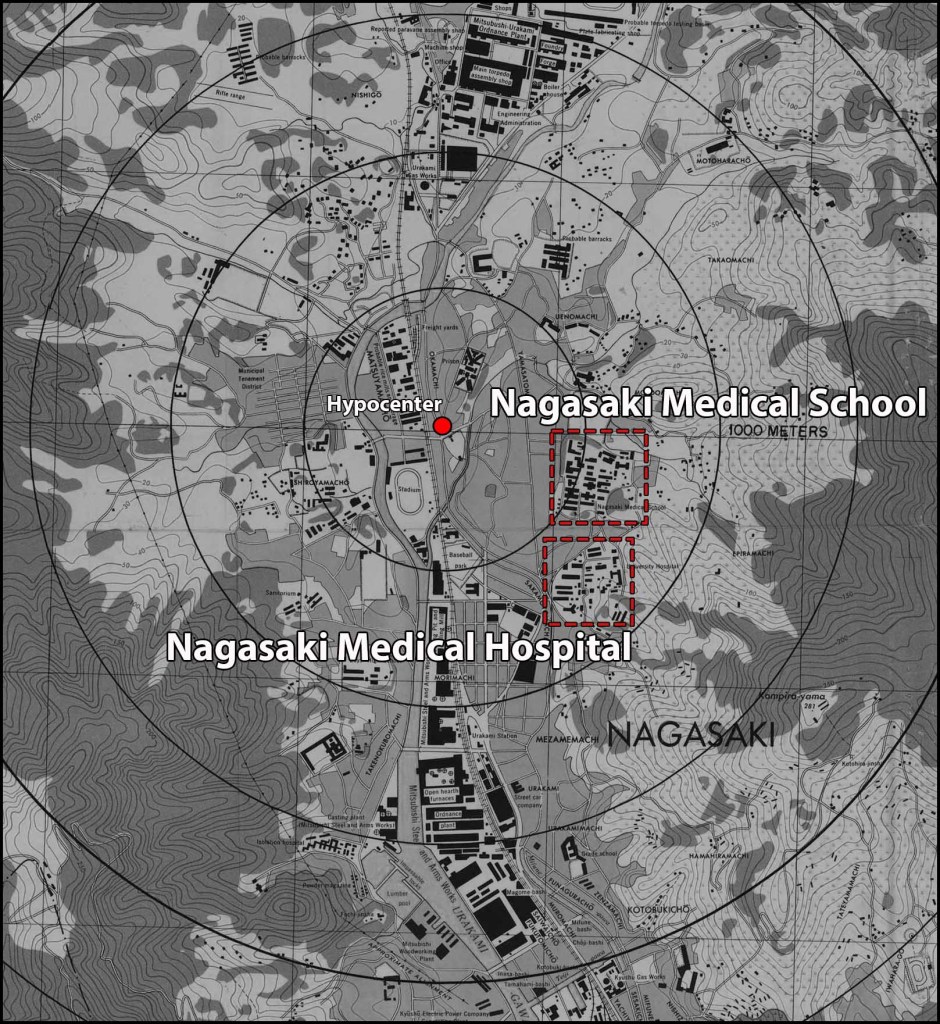

Although Fat Man, at approximately 21 kilotons, had a yield 30% higher than that of Little Boy, 16 kilotons, the damage done to Nagasaki as a whole was decidedly less than the damage done to Hiroshima. Post-mission photography would find that Fat Man had detonated almost two miles away from the original target point, but only a few hundred feet away from the stadium racetrack that Captain Beahan actually aimed at. The terrain where the explosion occurred, confined by hillsides in a valley, muted the lateral effects of the blast and lessened the damage done to the rest of the city. However, the 2.3- by 1.9-mile oval-shaped “bowl” of the Urakami Valley amplified the damage done to structures, which contributed to a greater degree of destruction in this area. The crew of Bockscar noticed this in the blast wave; they felt much stronger than those they experienced above Hiroshima.

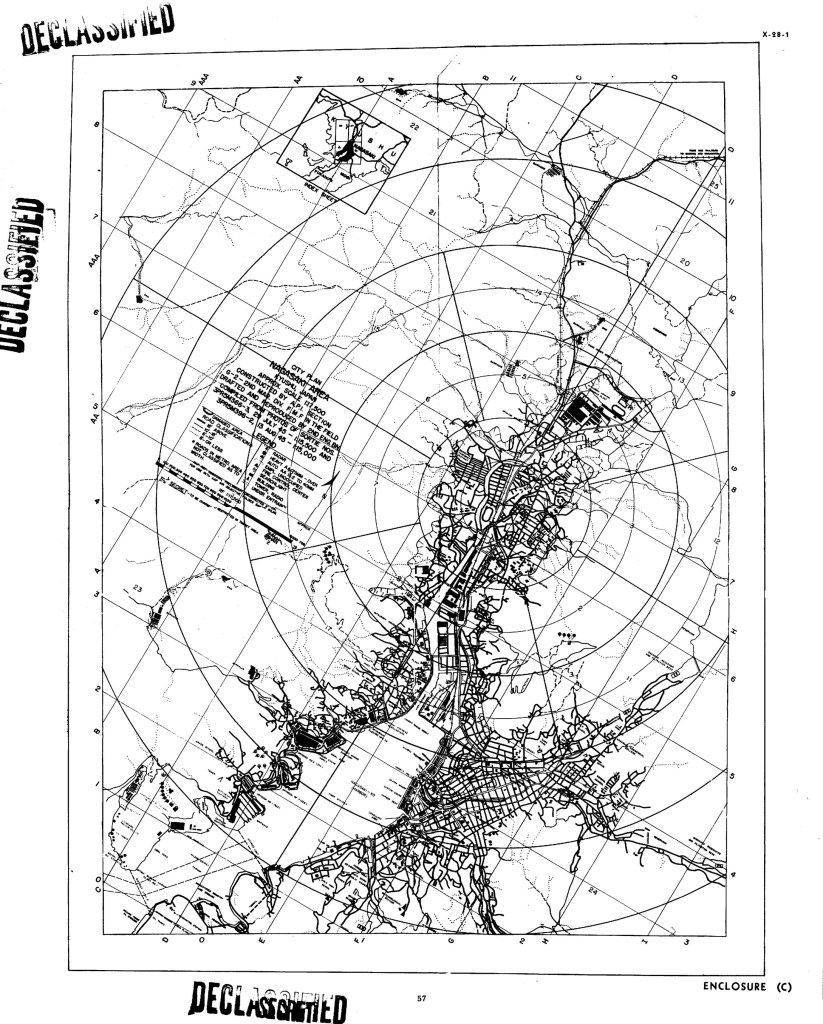

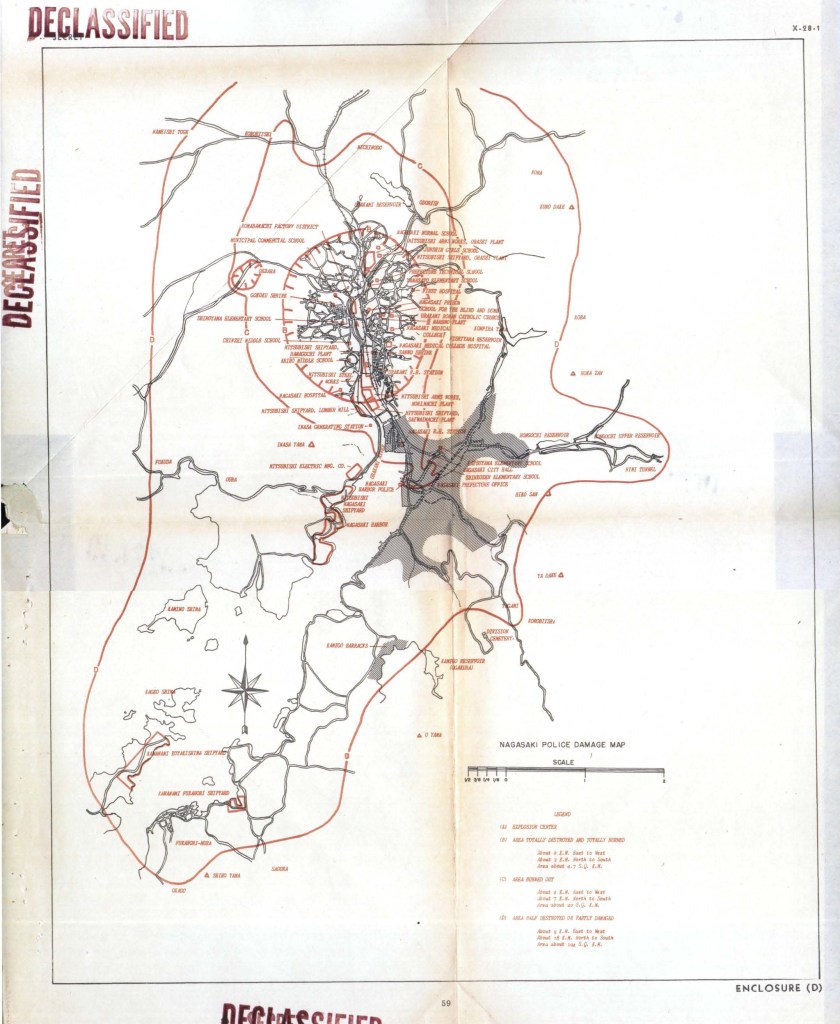

Due to the inclement weather that necessitated the use of Fat Man earlier than originally scheduled, initial aerial photo reconnaissance missions over Nagasaki returned little usable information. It was not until the week after the bombing that analysts were able to estimate that around 3.1 square miles (8 square kilometers, 44% of the city) had been severely damaged or destroyed. A later estimate by Nagasaki Prefecture reported 39.2% of homes and buildings in the city had been destroyed or damaged. The Manhattan Engineering District’s 1946 survey would determine that 2.9 square miles (7.5 square kilometers) of the city suffered very severe damage, 4.1 square miles (10.6 square kilometers) suffered moderate damage, and 35.8 square miles (92.7 square kilometers) suffered partial damage.

As described in the Manhattan Engineering District survey: “In the study of objects which gave definite clues to the blast pressure, such as squashed tin canes, dished metal plates, bent or snapped poles and the like, it was soon evident that the Nagasaki bomb had been much more effective than the Hiroshima bomb.” Had Fat Man exploded over its primary aiming point in the downtown area of the city, the entire Nakashima River Valley and all of Nagasaki’s waterfront would have also been completely leveled. General Doolittle had surmised as much during his brief meeting with Lieutenant Commander Ashworth and Major Sweeney.

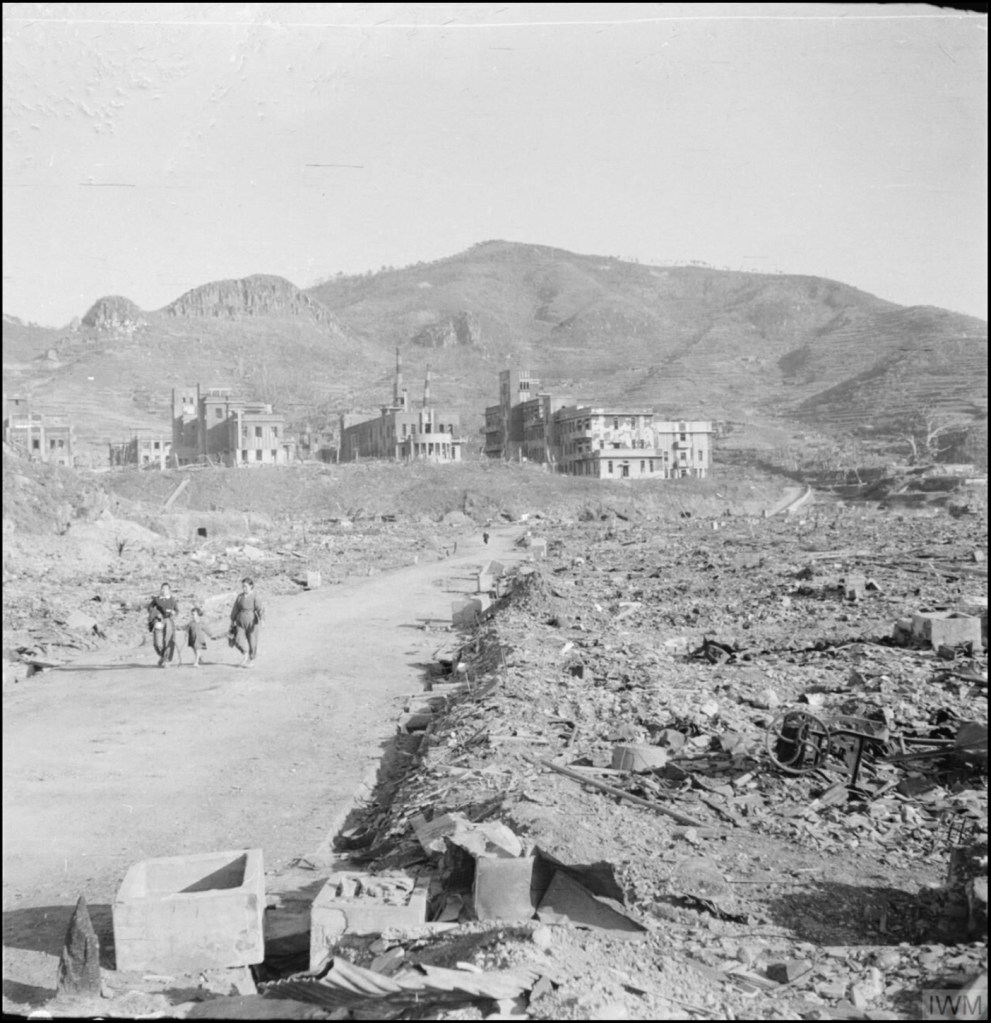

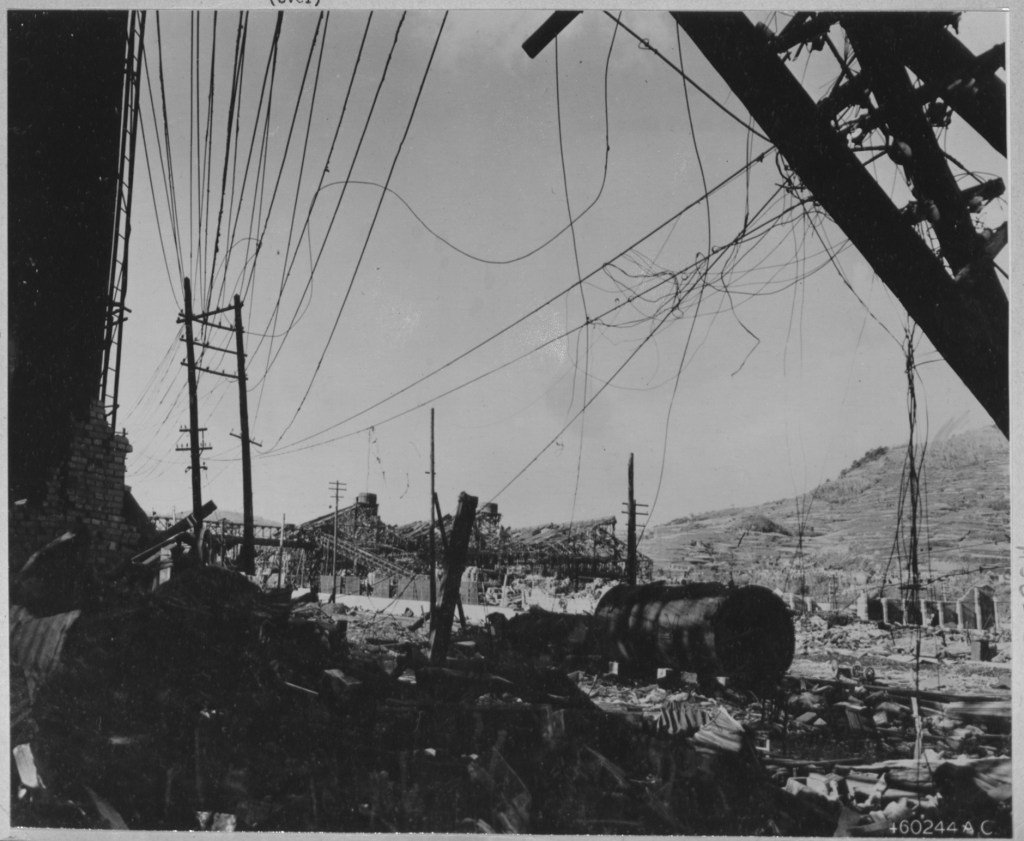

As the city tried to begin rescue efforts, they found the railroads were destroyed and the streets covered by debris consisting of stones, wood, plaster, glass, metal wiring, corrugated iron, tiles, the personal effects of victims, and the victims themselves. To reach the rest of the city, workers and the uninjured began clearing a 1.5-mile (2.4-kilometer) path in the road for one-lane traffic. This work was done by hand; much of the city’s heavy machinery was buried, destroyed, or part of the wreckage they were trying to clear. The main street was open to one-lane traffic by 15 August; a two-lane clearing was completed by 20 August. Somewhat luckily, much of the damage to the roads was superficial, with the most severe infrastructural damage done to the wooden bridges across the Urakami River and the railroad tracks that ran lengthwise through the valley.

Immaculate Conception Cathedral (Urakami Cathedral)

The hypocenter of the explosion was located in the town of Matsuyama near the Immaculate Conception Cathedral, one of the largest Christian congregations in the Far East, and Nagasaki Prison. The city of Nagasaki estimates that the Urakami Valley was home to around 15,000 of 20,000 Roman Catholics living in pre-bombing Nagasaki. At the time of the bombing, church services were being held in preparation for Ferragosto, today celebrated as the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, the day when Mary left the world and physically ascended to heaven, celebrated by the Catholic Church on 15 August.

The church was of very different construction than most of the buildings of Nagasaki, not only because of its Western architectural design, but also because it was made mostly of brick. On either side of the front doors were two bell towers, both topped with a solid dome and a cross. The blast completely destroyed the church’s roof and most of its walls, killing most, if not all, of the people attending the service. Only the facade still stood to distinguish it as a church. When the bell towers collapsed, both domes had fallen as well, but remained largely intact amidst the destroyed remains of the cathedral. A few hours later, fire had spread to the ruins and continued to burn into 10 August.

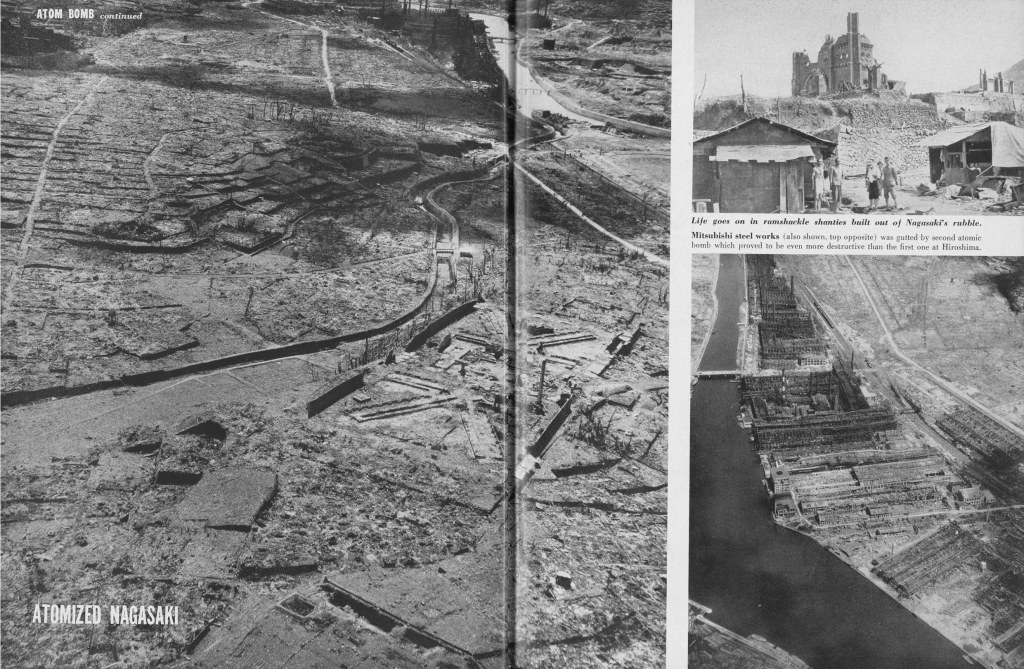

After the bombing, the residents of Nagasaki, now homeless and possessing few personal items, began to build small shacks out of the debris that now covered the city. These improvised shelters may have looked familiar to Americans who grew up in and around Hoovervilles of the Great Depression and were not meant to be permanent; it was the best the survivors could do with the materials available. When American military personnel and journalists made their way to Nagasaki after the war, many of these shacks were still standing. Due to how prolific they were throughout the Urakami Valley, many of the photographs from the post-war surveys feature the shelters and their inhabitants.

In the event of a conventional air raid with incendiary bombs, emergency and crisis planners began stockpiling supplies that included clothing, medicine, and food. These stockpiles were cached away in locations that were believed to offer protection in the event of mass fires in the city. The Urakami Cathedral was designated as a stockpile location due to its brick construction and location on a small rise above the surrounding terrain. Unfortunately, the Cathedral’s proximity to the hypocenter meant that these stores of rice, noodles, soy products, dried goods, and other necessities were destroyed along with the parishioners still in the building. Many of these caches were also located in concrete buildings, such as the Chinzei and Shiroyama Grade Schools located on the west side of the Urakami River, away from the most congested parts of the city.

Chinzei and Shiroyama National Schools

The Shiroyama Elementary School and the Chinzei Middle School, both of which were part of the Japanese National School public education program, were both located approximately 500 meters (546 yards) away to the west and southwest from the hypocenter and on the far side of the Urakami River.

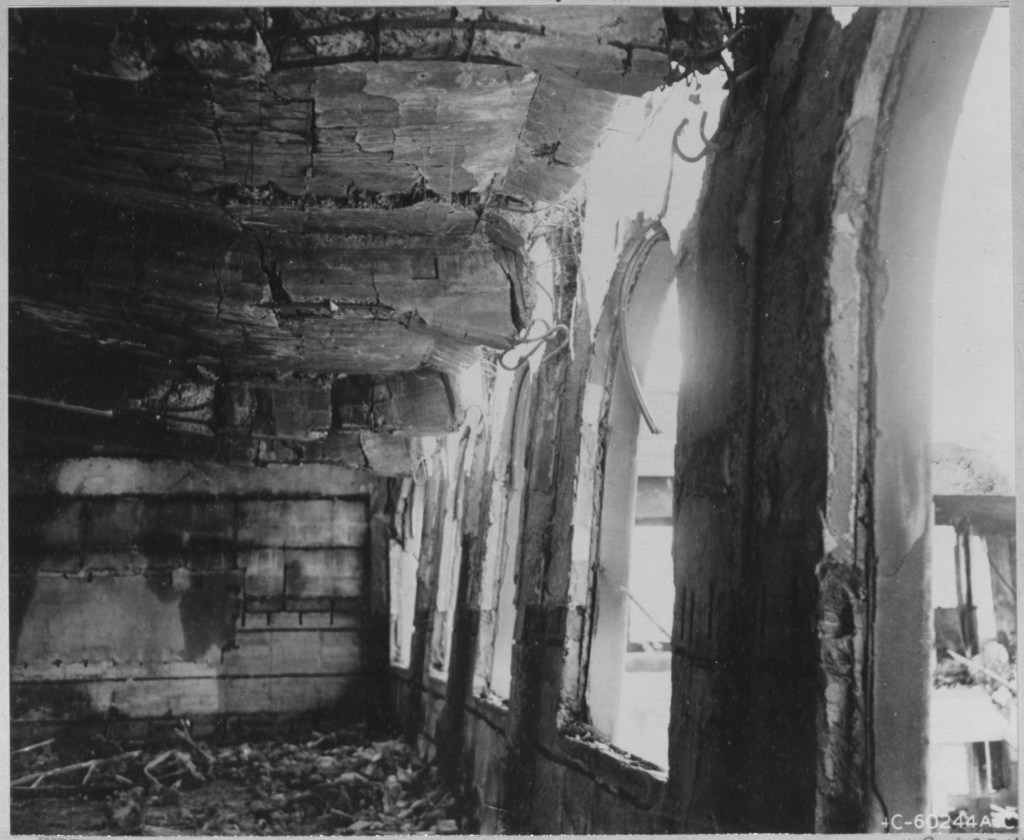

Shiroyama Elementary School was one of the more recognizable concrete structures in Nagasaki. The section in the middle of the building’s wings had windows shaped like round portholes, which differentiated it from the other concrete schools in the city. Additionally, the building was painted in a striped pattern designed to break up the building’s features from high altitudes. The central and west sides of the building survived, but its east wing, which faced towards the hypocenter, collapsed from the blast. Photos of the building’s interior show that the ceilings and exterior walls had buckled and were close to structural failure.

The Chinzei Middle School was located on the southern side of a prominent hill, around 80 feet (24 meters) overlooking the northern end of the Mitsubishi Steel Plant. It was built of reinforced concrete, making it more resistant to blast effects than many other buildings in Nagasaki. Its sturdiness also made it an ideal location as a sub-assembly plant for local industry and storage center for food and medical supplies. Most of the students had, by this point in the war, been allocated to working parties or sent into the countryside. The children old enough to work were taught how to use machine tooling to supplement the Mitsubishi industries. Unsurprisingly, the parts created by the students were not enough to turn around declining production rates as the United States steadily began to starve Japan of critical materials for warships, planes, tanks, and weapons.

After the atomic bomb dropped, the Chinzei School stood virtually alone on its small bluff. Its size and location made it one of the few recognizable landmarks in the Urakami Valley. Although the lower parts of the building’s structure were able to survive the explosion, the school’s fourth floor, as well as its roof, collapsed in on itself, reducing it to a three-story building. The falling concrete collapsed through the third and second floors, leaving the school almost entirely gutted. On the school’s western side, the walls of the top floor remained attached but leaning away from the blast.

The following schools were located in Nagasaki and were identified as having been damaged:

Nagasaki Normal School

Tamaura Middle School

Nagasaki Industrial Middle School

Nagasaki School for the Blind and Deaf

Commercial Municipal School

Mitsubishi Industrial School

Chinzei Middle School

Junshin Girls Middle School

Joshei Girls Middle School

The Theological School of Nagasaki

St. Maria’s Institute

Yamazato National School

Shiroyama National School

Nishiurakami National School

Nishizaka National School

Zenza National School

Fuchi National School

Nagasaki Medical University and Hospital

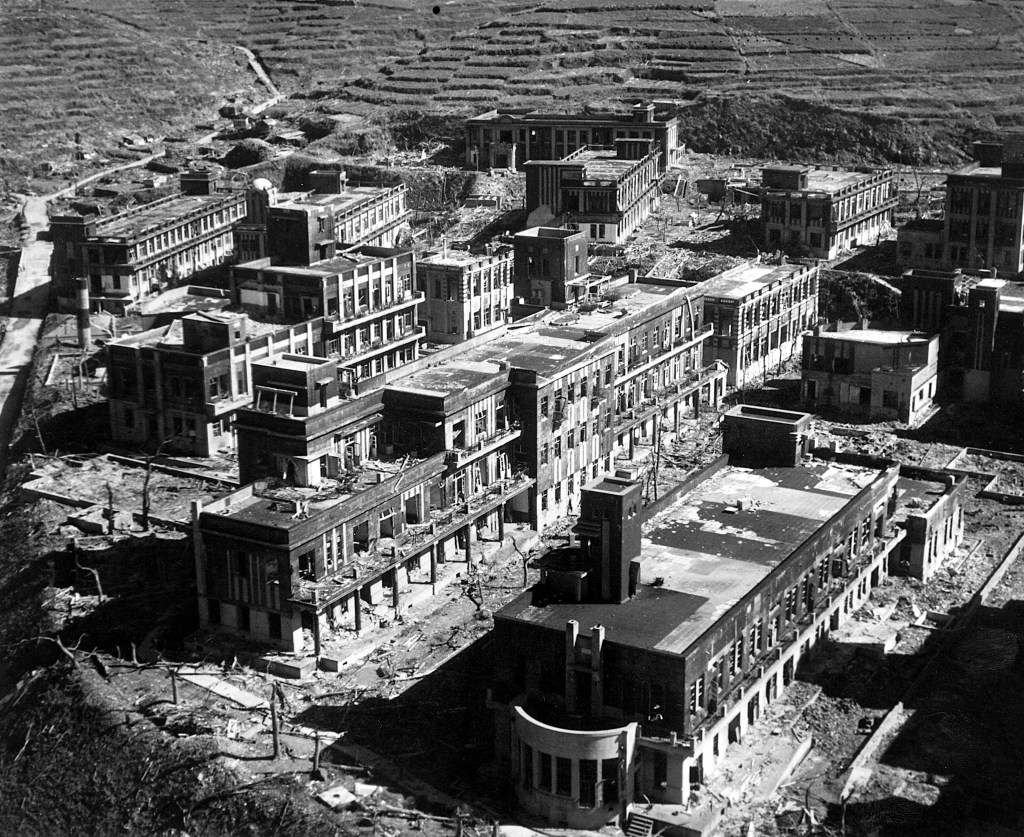

Due to its proximity to the hypocenter, the Nagasaki Medical Hospital was subjected to a large amount of intense radiation, heat, and overpressures. However, the hospital was one of the largest all-concrete campuses in Nagasaki. The building’s sturdy construction, including its thick walls, shielded the occupants from much of the damage. Even with the sturdily constructed buildings, the medical staff and patients near the windows facing the epicenter were still exposed to radiation as well as the shards of flying glass that shattered when the blast wave hit the hospital. One half of the medical staff at the hospital were killed with almost all of the survivors injured.

In an unpublished manuscript, Captain James F. Van Pelt, Bockscar’s navigator, wrote the following regarding his visit to Nagasaki as part of a post-war survey team: “… We went to the Medical School, a seven or eight story concrete building that did not look damaged from the outside, but inside was completely charred and burned. You could see people who had been operating with a skeleton on the table, some lying around the room and some in beds. The elevator was not running, the stairs were burned out and safes were blown.”

Despite surviving the bomb physically, the hospital was still devastated and virtually all medical work ceased for a time. As supplies and relief personnel from nearby locations like Sasebo and Omura Naval Hospital made their way to the ruins of Nagasaki, the wounded made their way to the few buildings still standing. The relief parties sent in the wake of the bomb were able to establish fifteen aid stations across the city. With most of the hospital’s facilities destroyed, the local military garrison worked to coordinate transportation for the survivors who needed urgent medical care. Thousands of casualties were sent to external facilities that included the Omura, Ishahaye, Ureshino, and Kawatana Naval Hospitals. On 16 August, the 216th Army Field Hospital from Komamoto was established as a temporary location to triage patients and coordinate the inflow and outflow of people and supplies. Civilian medical hospitals throughout Kyushu and Honshu also received patients from Nagasaki. However, many facilities in southern Japan were already receiving tens of thousands of casualties from Hiroshima.

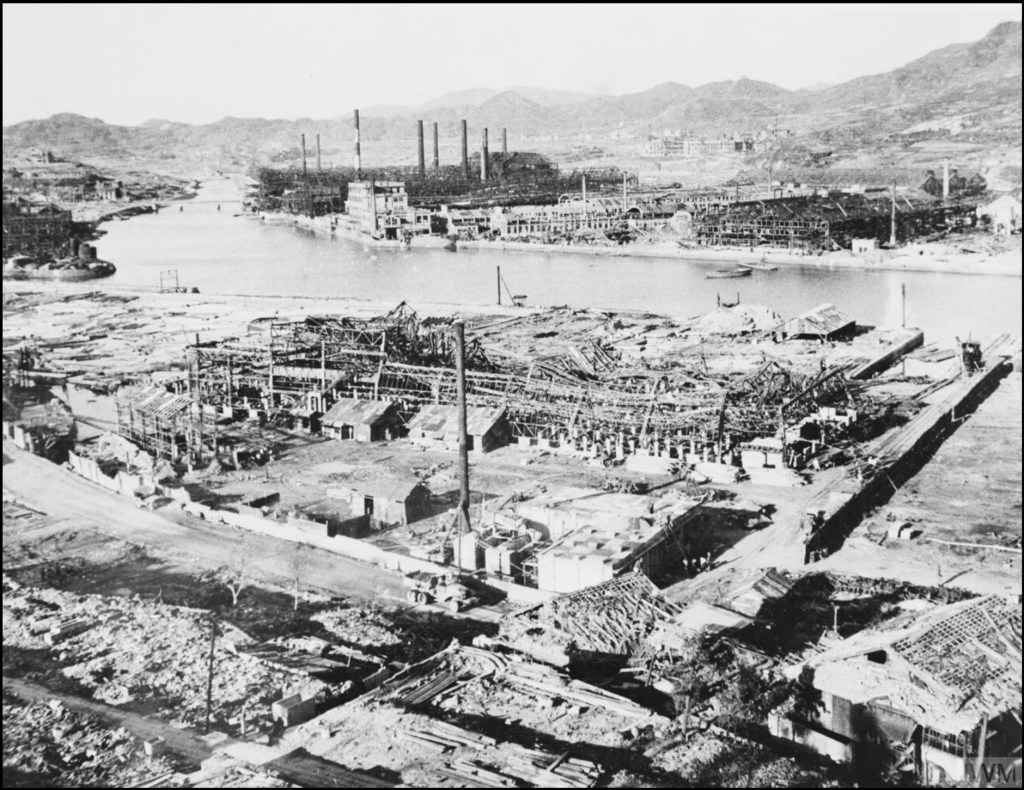

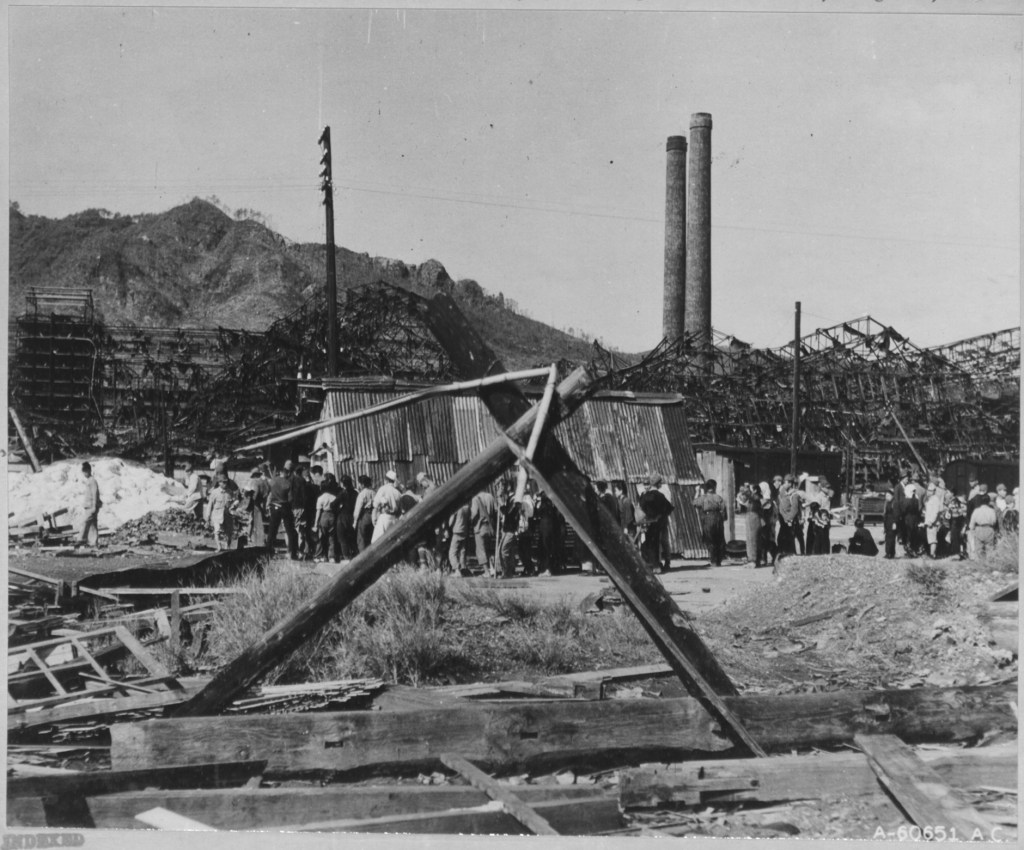

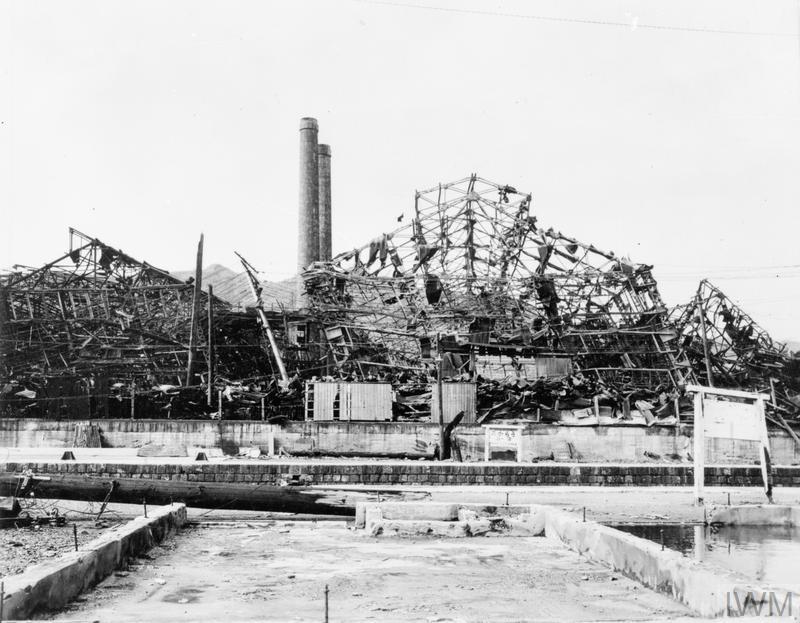

Mitsubishi Ordnance Plant and the Steel and Arms Works

Even though the bomb was around two miles from the planned target, its placement in the Urakami Valley was roughly midway between the Mitsubishi Arsenal and the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, both of which were major targets. Buildings at both locations were either destroyed or heavily damaged. The damage was described in the Nagasaki Prefectural Report:

“The strong complex steel members of the structures of the Mitsubishi Steel Works were bent and twisted like jelly and the roofs of the reinforced concrete National Schools were crumpled and collapsed, indicating a force beyond imagination…”

The Strategic Bombing surveyors estimated that the damages done to both plants were around 50%. Mitsubishi officials at the Torpedo Works and Steel Plant estimated that damages were around 58% and 78%, respectively. The Naval Commander of the Sasebo Naval District, who had also commissioned a report on the bombing, estimated that, even though most of the industrial machinery was unusable immediately post-bombing, they would eventually be able to return to around a production level of 70%. However, because the war was over, demand for war-time production plummeted. Consequently, many of the Mitsubishi production facilities remained untouched and unrepaired years after the end of the war.

Damage to the Torpedo Works was amplified by the post-bombing fires that began spreading through the rubble. With the city’s northern gas works located in the proximity to the facility, gas lines that were broken in the blast began to leak and fire soon engulfed the production complex. Explosives and propellant used in the manufacture of the torpedoes began to cook off, causing further damage. By then, most of the workers who survived the bomb had left to go home and look for family members.

“As intended, the bomb was exploded at an almost ideal location over Nagasaki to do the maximum damage to industry, including the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works (Torpedo Works), and numerous factories, factory training schools, and other industrial establishments, with a minimum destruction of dwellings and, consequently, a minimum amount of casualties.”

Strangely enough, the 1946 report by the Manhattan Engineering District quoted above makes it seem like the bomb was supposed to be dropped on the Urakami Valley instead of two miles south of the actual hypocenter. Although it also describes “a minimum amount of casualties,” it was known that the casualty count was in the tens of thousands for both cities individually. With the two cities combined, survey groups from the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan understood that they were looking at casualty figures in excess of 100,000. Unfortunately, the severity of the damage and destruction inflicted upon the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ensured that the actual numbers of dead and wounded would never be known.