The End of the War

Even with the second atomic bombing and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war, and with no official word of Japan’s surrender, leaders of the military and President Truman’s cabinet began planning for the third atomic bombing mission. The team at Los Alamos were casting the third plutonium core and preparing it for shipment to Tinian. It was to be delivered by the 509th Group’s Deputy Commander Lieutenant Colonel Thomas J. Classen, who had returned to the States prior to the Nagasaki mission. On Tinian, the Project Alberta personnel were assembling the last Fat Man unit, F-32, and preparing its gadget for delivery, scheduled for sometime after 24 August 1945.

Although Kokura and Niigata were still available, Admiral Purnell, Captain Parsons, and General Farrell recommended Tokyo as the next target city for the third atomic bombing. Their line of thinking held that Tokyo was essentially a burned up husk, with relatively few Japanese civilians remaining in the area. However, dropping the bomb over Tokyo’s environs, such as Chiba, Kawasaki, Yokohama, or Tokyo Bay, would give Emperor Hirohito and his entire government a front-row seat to view the power of America’s new bomb without a casualty list as high as it would be in a city that was more or less intact, a factor that appeared to weigh heavily on President Truman’s conscience. An alternate list, created by planners of the 20th Air Force, proposed six cities for atomic bombing: Sapporo, Hakodate, Oyabu (possibly referring to Oyabe in Toyama Prefecture), Yokosuka, Osaka, and Nagoya. Reaching Sapporo and Hakodate, located on the northernmost Japanese island of Hokkaido, would require transferring the 509th from Tinian to Okinawa.

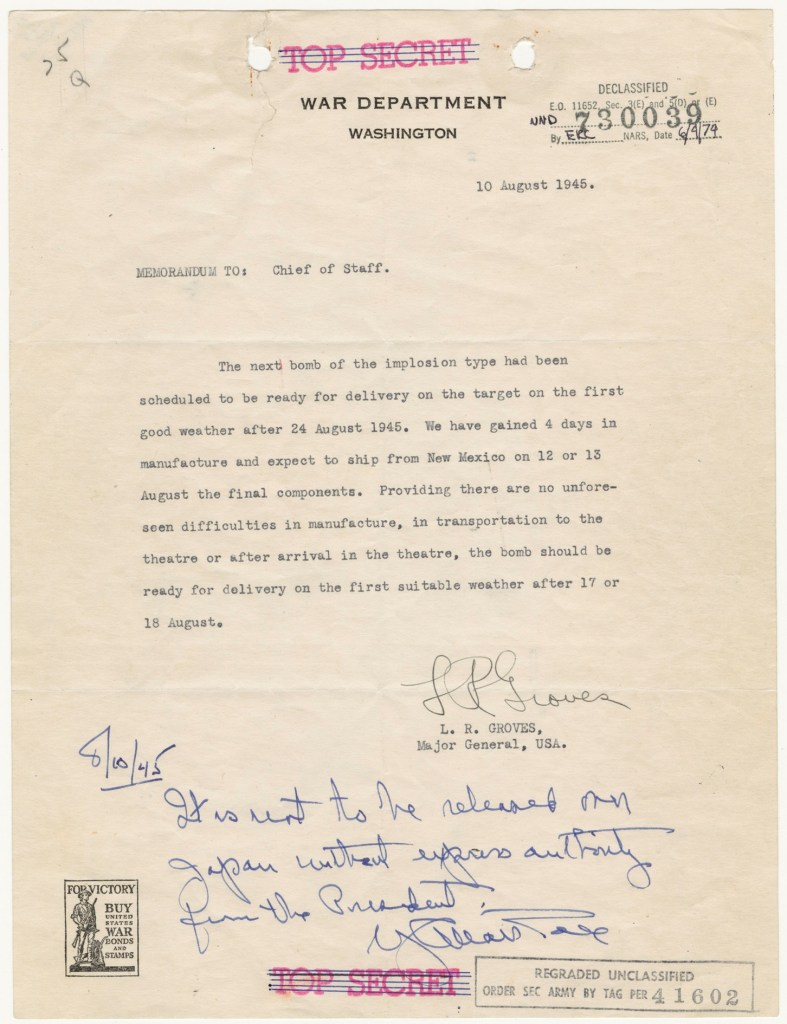

In a memo sent to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, General Groves indicated that they would be able to move up the next atomic bombing to soon after 17 August. Reflecting what may have been President Truman’s growing understanding of what the atomic bombs were capable of, General Marshall issued a directive stating that the President alone would be the approval authority for any subsequent atomic bombings. Although this action may have appeared at the time to be just another part of a war-time government’s machinations, it would prove to have a lasting effect on the military’s nuclear policy: the President, as the Commander in Chief of the United States Armed Forces, held sole authority to direct the combat deployment of nuclear weapons.

10 August 1945.

Memorandum To: Chief of Staff.

The next bomb of the implosion type had been scheduled to be ready for delivery on the target on the first good weather after 24 August 1945. We have gained 4 days in manufacture and expect to ship from New Mexico on 12 or 13 August the final components. Providing there are no unforeseen difficulties in manufacture, in transportation to the theatre or after arrival in the theatre, the bomb should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or 18 August.

L. R. Groves, Major General, USA.

8/10/45

It is not to be released on Japan without express authority from the President.

[George C. Marshall]

In the days following the mission on Hiroshima, newscasters on the radio focused much of their air time on reporting the declassified aspects of the Manhattan Project: Los Alamos, the Clinton and Hanford Engineering Works, the Trinity Test, and the damage done to the entire city of Hiroshima by a single plane flying tens of thousands of feet in altitude. “Atomic Energy for Military Purposes: A General Account of the Scientific Research and Technical Development That Went Into the Making of Atomic Bombs,” usually referred to as “The Smyth Report” after its writer Henry D. Smyth, consisted of a curated narrative and timeline of the Manhattan Project history and processes up to the Trinity Test. Great care was taken to ensure that the information used in the report would not contain any classified aspects of the Project.

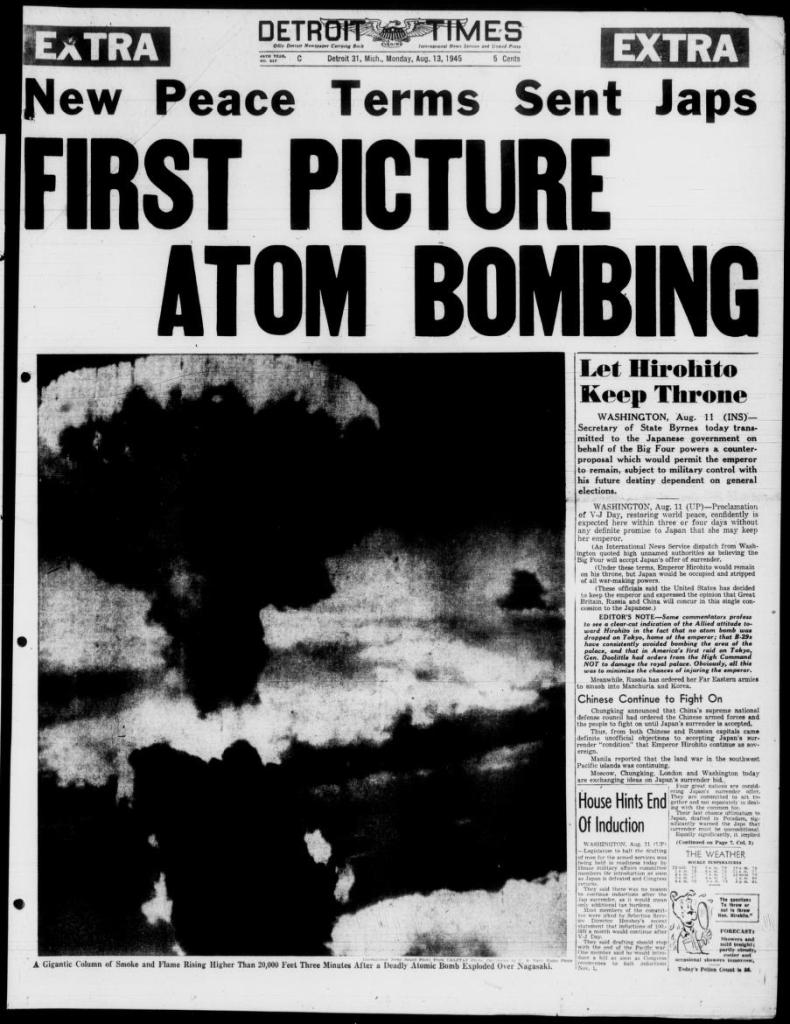

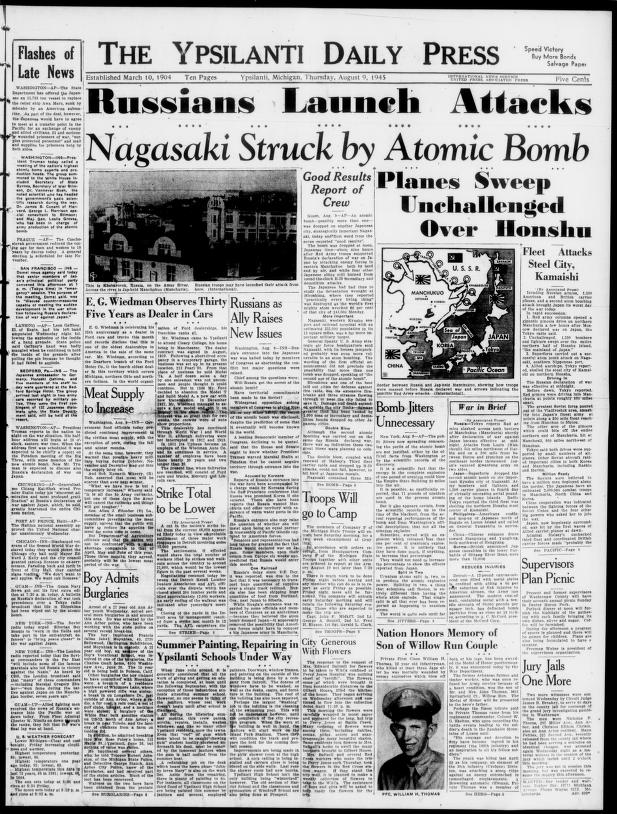

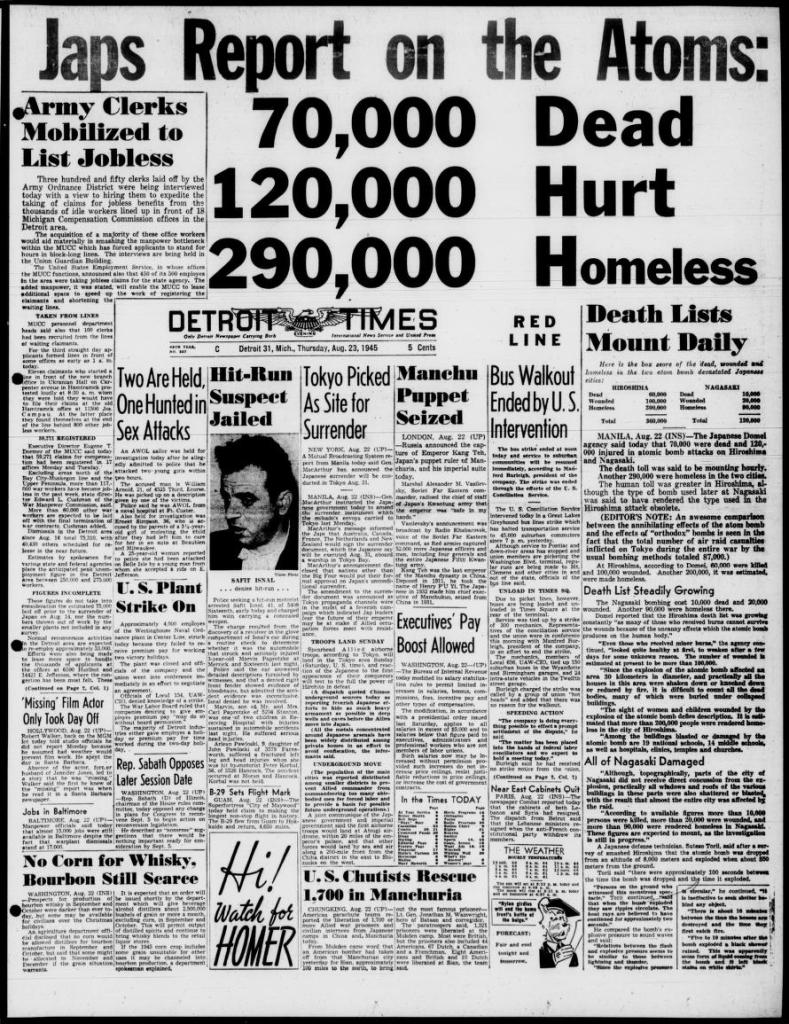

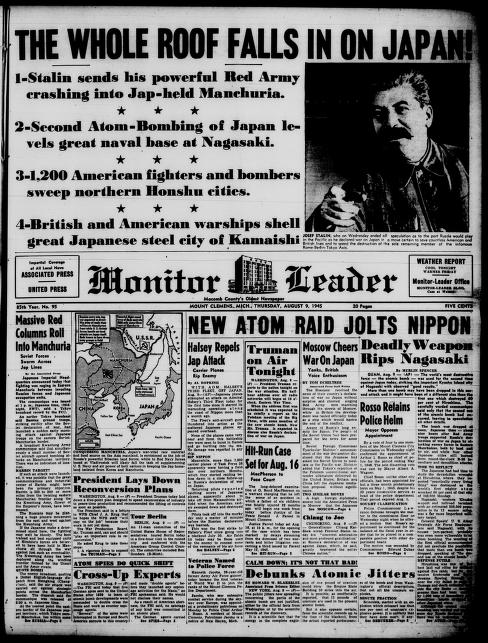

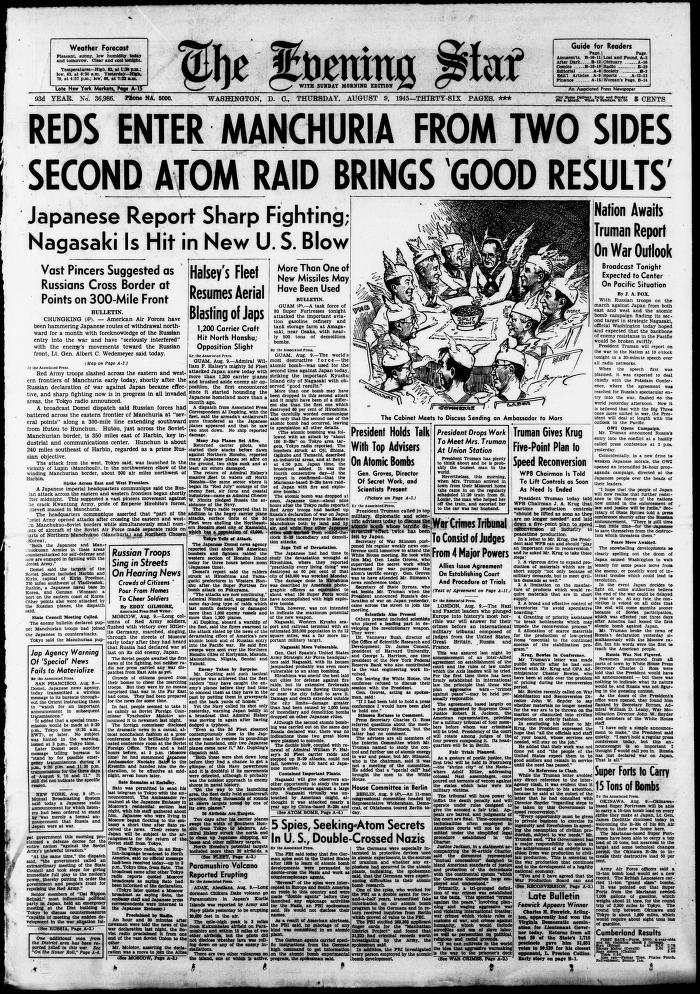

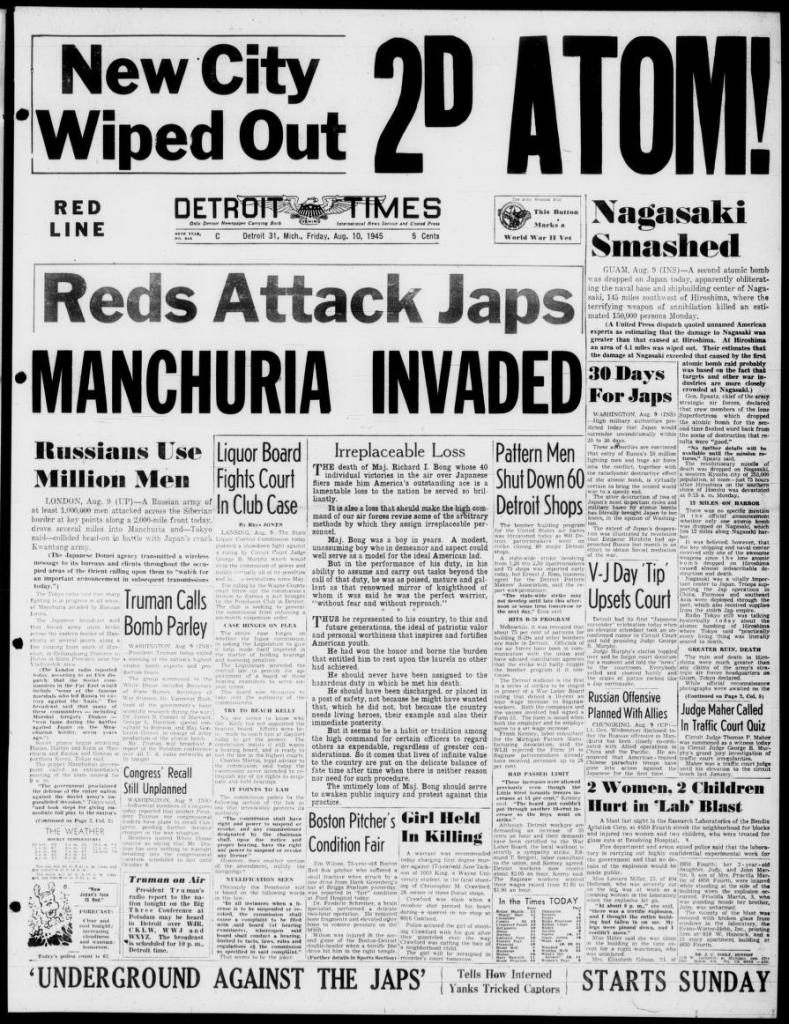

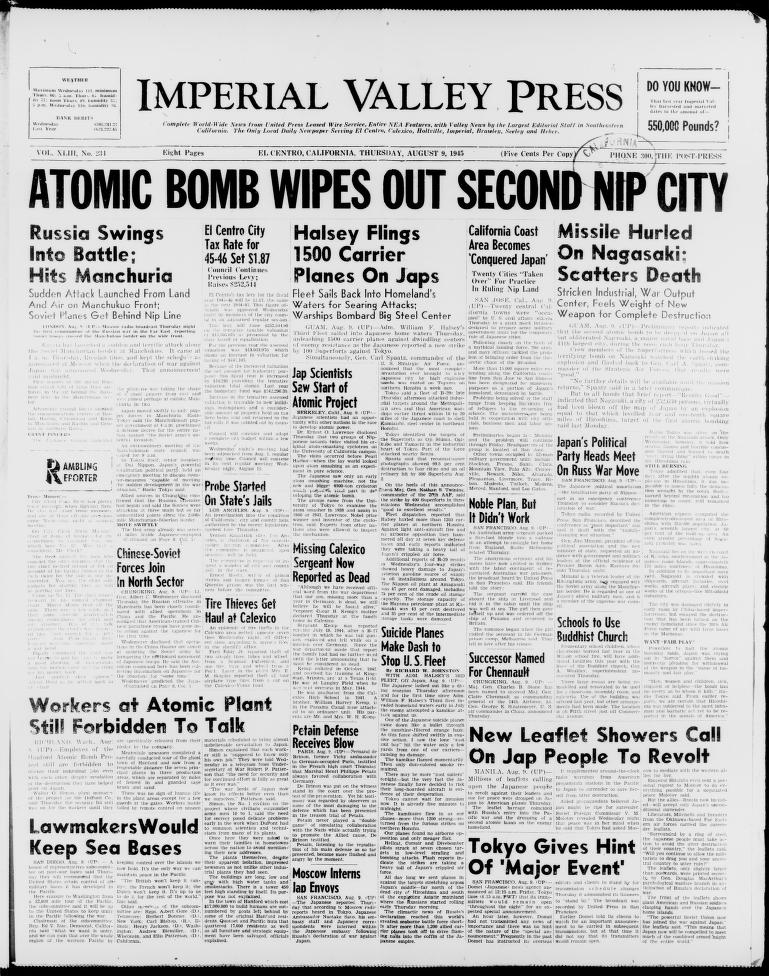

During the middle weeks of August 1945, American newspapers ran front page news of the atomic bombings, the Soviet Union’s entrance into the war against Japan with the invasion of Manchuria, and rumors that the Japanese government was ready to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, albeit with a few caveats related to the status of Emperor Hirohito.

In early September, American and Allied personnel began flooding into Japan in order to establish the military occupation that would last until 1952. The United States also sent in multiple survey teams to record damages, casualty statistics, and other effects related to the atomic bombs. As a part of this effort, two hospital ships, the USS Sanctuary and USS Haven were dispatched to Nagasaki to augment the Japanese medical effort in the city. Medical personnel were given training on radiation sickness and worked to provide supplies that had run out in Japan before the war ended.

Nagasaki served as one of the primary embarkation and debarkation ports for prisoners of war, many of whom would need long term care. Trains crowded with Australians, British, Chinese, Koreans, and Americans made their way south through the still-shattered remains of the Urakami Valley on their way to Nagasaki Bay and transport ships waiting to take them home.

Work began on treating prisoners of war and slave laborers whose health had severely declined following their incarceration and deportation to labor camps in Japan. Some of them had been Japanese prisoners for years. Among the prisoners were civilians and military personnel who had been captured in the first months following the United States’ entry into the war from the campaigns on Wake Island, the Philippines, Malaysia and Singapore, and New Guinea. At the time, the Japanese Empire seemed to be unstoppable. It had conquered one-sixth of the world’s surface and seized most of East and Southeast Asia from the western powers. Now, in 1945, the Japanese Empire had shrunk to the mainland, its cities and industries had been reduced to rubble, and there were now foreign soldiers, sailors, and marines occupying the Land of the Rising Sun.

After the end of the occupation of Japan in April 1952, photographs began circulating in various publications showing an account of the atomic bombings on the ground. In their 29 September 1952 edition, Life featured six pages of graphic photographs showing the dead and injured victims of the atomic bomb. These images and similar ones from Hiroshima were almost entirely censored by General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters in an effort to avoid unrest and anti-American sentiment in Japan while the occupation was ongoing. Seeing the graphic images of Japan’s atomic bombed cities may have evoked a poignant reminder of the world situation in 1952 and the devastating possibilities for the future. Once the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb (essentially a Fat Man gadget) in 1949, the United States could no longer claim an atomic monopoly. The Cold War had gone hot on the Korean Peninsula and the arms race meant that nuclear weapons technology was becoming evermore prolific and sophisticated. Perhaps Life Magazine itself stated the reality the best:

“To a world building up its stock of atomic bombs, the people of the two cities warn that the long suppressed photographs, terrible as they are, still fall far short of depicting the horror which only those who lived under the blast can know.”

Life Magazine, Vol. 33, No. 13, 29 September 1952.

More Resources and Information

Some of the most striking images from Nagasaki came from Japanese military photographer Yosuke Yamahata. He was on the ground in Nagasaki almost immediately after the bombing. On 10 August alone, Yamahata took almost one hundred photographs. His striking images are about as close as one can get to the aftermath of the atomic bombing without being a hibakusha. These photographs have been in exhibits around the world, including one titled “Nagasaki Journey Archive: The Photographs of Yosuke Yamahata” at the Museum of Photographic Arts at the San Diego Museum of Art, which you can view using the link below:

You can also find one of the most comprehensive galleries showing the atomic bombing of Nagasaki online through the Google Arts & Culture platform’s partnership with the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.

You can also view the English version of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum’s website online. They also have a searchable online database containing photographs, artifacts, artwork, and more. The Nagasaki Archive has an interactive Google Earth project that features Nagasaki hibakusha, their recollections of the bombing, and their location relative to the hypocenter.

For a more holistic view of the Manhattan Project, the US Department of Energy has an interactive history available through the Office of Scientific and Technical Information’s website.