The “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 9th Cavalry

With the completion of the Civil War, Congress reorganized the Army and created six African-American units. These units, commanded by white officers, were the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments and the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st Infantry Regiments. A force reduction in 1869 dropped two of the Infantry regiments and allowed for only two – the 24th and 25th. Many career Army officers, as well as those gaining commissions after the Civil War, held deep racial prejudices – George Armstrong Custer refused when given a chance to command African-American troops – and would not volunteer for the new units. Soldiers enlisted for a period of 5 years and received $13 a month pay, plus room, board and clothing.

The Army in the West consisted of no more than 25,000 men at any time, with just under 12 percent being African-Americans who participated in roughly 13 percent of all skirmishes and battles during the Indian Wars of 1866 to 1897. Of particular note are the campaigns on the southern plains in 1877, against the Apache from 1879 to 1881, and the Pine Ridge campaign from 1890 to 1891. During this time, 18 African-American soldiers received the Medal of Honor.

The 9th Cavalry Regiment was formed 21 July 1866 in the Regular Army as Troop D, 9th Cavalry. On August 3, 1866, Major General Philip H. Sheridan, commanding the Military Division of the Gulf, was authorized to raise one regiment of African-American cavalry to be designated the 9th Regiment of U. S. Cavalry; it was organized on 21 September 1866 in New Orleans, Louisiana, and mustered between September 1866 and 31 March 1867. Its first commanding officer was Colonel Edward Hatch – he would remain with the regiment until his death in 1889. The mustering, organized by Major Francis Moore, 65th US Colored Infantry, formed the nucleus of the enlisted strength, with men enlisting from New Orleans and its environs. In the autumn of 1866, recruiting began in Kentucky, which also provided soldiers to the 9th.

The nucleus of the new units – the non-commissioned officers – were typically men who had served with the “Colored Regiments” during the Civil War and were familiar with Army life and customs. Southern laws had prohibited slaves being educated so most of the men were illiterate. Some of those enlisted from the northern areas, particularly by the 10th Cavalry, had some rudimentary education, but for many in the 9th, it was only with some difficulty that men were found who could perform the duties as clerks and orderlies for the regiment – junior officers performed most of these tasks in the first months or year of the regiment’s existence.

Understanding the educational needs of these soldiers, Chaplains were tasked with educating the enlistees in addition to performing their typical religious duties. Army policy also changed – where previously Chaplains were assigned to a particular post, each of the new black regiments was assigned its own Chaplain with the additional duties of teaching literacy. Two of these chaplains had served with the Colored Regiments during the Civil War.

The horses were obtained in St. Louis, Missouri and the companies (also referred to as troops in cavalry units) were soon all assembled in New Orleans, housed in empty cotton presses as barracks. A cholera epidemic resulted in the Regiment’s movement to Carrolton, a New Orleans suburb. By the end of March 1867, the Regiment was at nearly full strength, with a total of 885 enlisted men. A common misconception is that that the black regiments received inferior stock and supplies — this was not true. Hatch, himself, was often responsible for deciding which stock suppliers would provide mounts for his men, turning down numerous unscrupulous purveyors of stock due to inferior animals. Quite often the number of mounts available was less than required, or the quality was inferior, but this was a common problem for all cavalry units – black or white – throughout the West.

The Army tasked the 9th with important missions in protecting the frontier and engaging “renegade Indians” and certainly had nothing to gain in purchasing inferior animals for the new regiments. The same situation existed with weapons. As new rifles were invented and manufactured, they quickly made their way to the black regiments – the 38th Infantry Regiment received over 600 of Springfield’s new breech-loaders soon after manufacture and in 1874, four troops of the 9th were issued new Model 1873 Springfield rifles as well as newly developed Colt revolvers being issued to two troops. By March of 1875, all troops of the 9th had the new weapons.

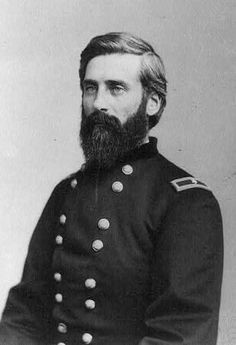

Colonel Edward Hatch

Colonel Edward Hatch was born December 22, 1832 in Bangor, Maine and attended Norwich Military Academy in Northfield, Vermont. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he was in the lumber business in Muscatine, Iowa. He initially volunteered to serve in the Union Army as a Private. He helped raise the 2nd Iowa Cavalry, rising to the rank of Major and by June 1862 had been promoted to Colonel. His Civil War career was quite notable, as he eventually rose to command the Army of the Tennessee’s Cavalry Regiment. In 1863, he assisted Colonel Benjamin Grierson’s 6th Illinois Cavalry on a raid through Mississippi with the purpose of distracting Confederate troops from Grant’s campaign against Vicksburg. Grierson would later command the other battalion of African-American cavalry, the 10th Cavalry regiment, and the men would work closely for years. “The raid earned Grant’s admiration and his later support for Grierson and Hatch as Colonels in the regular Army.”

The Battle of Nashville, in December 1864, demonstrated Hatch’s valor and strength as a cavalry commander. During the battle, his men attacked up the fortified Brentwood Heights and attacked the Confederates in their rear area, capturing twenty-seven field guns in two days and taking several hundred prisoners. Major General James H. Wilson would write of Hatch that he had a “splendid constitution and striking figure,” and “Only had to be told what he was to do and then attended to the rest himself.” However, he also stated that “he always declared himself ready without reference to feed, forage or ammunition.” Unfortunately, this fault was to affect the perception of his performance and the condition of his men and mounts during the Victorio campaign.

With the establishment of the African-American regiments in accordance with the 1866 Army Reorganization Act, Hatch was recommended as one of two commanders of the cavalry troops and quickly accepted. In New Mexico, Hatch became an advocate of having the Warm Springs Apache remain on the reservation at Ojo Caliente, and wrote numerous times about the situation at the reservation – quickly gaining an understanding that the lack of provisioning provided by the Indian Bureau was a primary reason for Victorio and his men raiding into southern New Mexico and northern Mexico. In a letter dated February 14, 1880 to the Assistant Adjutant General, Department of the Missouri, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, he wrote:

In compliance with direction contained in your letter of the 7th instant, I have the honor to report in regard to the hostilities of Victorio and his band as follows-

My attention was first called to those Indians about April 26th, 1876. The Indians had left the Fort Bowie (Arizona) Reservation and were Killing people and stealing horses; I was also informed that there was a possibility of the Hot Springs Indians going with them owing to the fact that no Beef having been issued to them by their Indian Agent at Ojo Caliente.

After ordering out Troops to intercept these Indian raiding parties, I at once proceeded to the Hot Spring Agency at Ojo Caliente, where I found the Indians actually preparing for the War Path and going to Mexico – the reason was, they were not fed.

Hatch met with Victorio several times, considering both him and Nana friends, each time the lack of provisioning was given as the main reason for continued raiding. Once President Grant’s “Peace Policy” was implemented, all Apache would be moved to the San Carlos reservation in Arizona. Hatch attempted to influence the Department of the Interior, under which the Indian Bureau belonged, to rescind the decision and keep Victorio and his people at Ojo Caliente, to no avail.

On February 13, 1880, the Council and House of Representatives of the Territory of New Mexico passed a joint resolution regarding Hatch’s conduct – and that of his men – in the territory. It stated, among other items,

Resolved: That the energetic and soldierly manner with which the Military Affairs of this Territory has been managed by Colonel Edward Hatch, Ninth Cavalry, Brevet Major General, U.S. Army and the efforts made by him to render our territory safe for Settlers and Miners and the distinguished conduct in managing Indian affairs, all have added Fresh Lustre to the reputation of the United States Army and deserve recognition by the people of the Territory.

Hatch spent his entire regular Army career as commander of the 9th Cavalry Regiment. In 1881, the regiment moved to Fort Riley, Kansas, then, four years later, to Fort Robinson, Nebraska. Colonel Hatch died on April 11, 1889 at Fort Robinson – eight of his senior NCO’s escorted his body to Fort Leavenworth for burial.