About Trinity Site

The story of Trinity Site begins with the formation of the Manhattan Project in June 1942. The project was given overall responsibility for designing and building an atomic bomb. At the time, it was a race to beat the Germans who, according to intelligence reports, were building their own atomic bomb.

Under the Manhattan Project, three large facilities were constructed. At Oak Ridge, Tennessee, huge gas diffusion and electromagnetic process plants were built to separate uranium-235 from its more common form, uranium-238. Hanford, Washington became the home for nuclear reactors which produced a new element called plutonium-239. Both uranium-235 and plutonium-239 are fissionable and can be used to produce an atomic explosion.

Los Alamos was established in northern New Mexico to design and build the bomb. At Los Alamos, many of the greatest scientific minds of the day labored over the theory and actual construction of the device. The group was led by Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who is credited with being the driving force behind building a workable bomb by the end of the war.

Los Alamos scientists devised two designs for an atomic bomb, one using uranium-235 and another using plutonium-239. The uranium bomb was a simple design and scientists were confident it would work without testing. The plutonium bomb was more complex and worked by compressing the plutonium into a critical mass which sustains a chain reaction. The compression of the plutonium ball was to be accomplished by surrounding it with lens-shaped charges of conventional explosives. They were designed to all explode at the same instant. The force is directed inward, thus smashing the plutonium from all sides.

In an atomic explosion, a chain reaction picks up speed as atoms split, releasing neutrons plus great amounts of energy. The escaping neutrons strike and split more atoms, thus releasing still more neutrons and energy. In a nuclear explosion, this all occurs in a millionth of a second with billions of atoms being split.

Project leaders decided a test of the plutonium bomb was essential before it could be used as a weapon of war. From a list of eight sites in California, Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado, Trinity Site was chosen as the test site. The area already was controlled by the government because it was part of the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range, which was established in 1942. The secluded Jornada del Muerto was perfect as it provided isolation for secrecy and safety, but was still close to Los Alamos.

Beginnings of Trinity Site

In the fall of 1944, soldiers starting arriving at Trinity Site to prepare for the test. Marvin Davis and his military police unit arrived from Los Alamos at the site on 30 December 1944. The unit set up security checkpoints around the area and had plans to use horses to ride patrol. According to Davis, the distances were too great and they resorted to jeeps and trucks for transportation. The horses were sometimes used for polo, however. Davis said that Captain Bush, Base Camp Commander, somehow got the soldiers real polo equipment to play with, but they preferred brooms and a soccer ball.

Other recreation at the site included volleyball and hunting. Davis said Captain Bush allowed the soldiers with experience to use the Army rifles to hunt deer and pronghorn. The meat was then cooked up in the mess hall. Leftovers went into soups which Davis said were excellent.

Of course, some of the soldiers were from cities and unfamiliar with being outdoors in the American southwest. Davis said he went to relieve a guard at the Mockingbird Gap post and the soldier told Davis he was surprised by the number of “crawdads” in the area considering it was so dry. Davis gave the young man a quick lesson on scorpions and warned him not to touch.

Throughout 1945, other personnel arrived at Trinity Site to help prepare for the test. Carl Rudder was inducted into the Army on 26 January 1945. He said he passed through four camps, attended basic for two days, and arrived at Trinity Site on 17 February. On arriving, he was put in charge of what he called the “East Jesus and Socorro Light and Water Company.” It was a one-man operation, himself. He was responsible for maintaining generators, wells, pumps, and doing the power line work.

A friend of Rudde, Loren Bourg, had a similar experience. He was a fireman in civilian life and ended up trained as a fireman for the Army. He worked as the station sergeant at Los Alamos before being sent to Trinity Site in April 1945. In a letter, Bourg said, “I was sent down here to take over the fire prevention and fire department. Upon arrival I found I was the fire department, period.”

As the soldiers at Trinity Site settled in, they became familiar with Socorro. They tried to use the water out of the ranch wells but found it so alkaline they couldn’t drink it. In fact, they used Navy salt-water soap for bathing. They hauled drinking water from the fire house in Socorro. Gasoline and diesel was purchased from the Standard bulk plant in Socorro.

According to Davis, they established a post office box, number 632, in Socorro so getting their mail was convenient. All the trips into town also offered them the chance to get their hair cut in the barbershop in town. If they didn’t use the shop, Sergeant Greyshock used horse clippers to trim their hair.

Jumbo

The bomb design to be used at Trinity Site actually involved two explosions. First, there would be a conventional explosion involving the TNT and then, a fraction of a second later, the nuclear explosion, as long as a chain reaction was maintained. The scientists were sure the TNT would explode, but were initially unsure of the plutonium core. If the chain reaction failed to occur, the TNT would blow the very rare and dangerous plutonium all over the countryside.

Because of this possibility, Jumbo was designed and built in Ohio. Originally, it was 25 feet long, 10 feet in diameter, and weighed 214 tons. Scientists were planning to put the bomb in this huge steel jug because it could contain the TNT explosion if the chain reaction failed to materialize. This would prevent the plutonium from being lost. If the explosion occurred as planned, Jumbo would be vaporized.

Jumbo was brought to Pope, New Mexico, by rail and unloaded. A specially-built trailer with 64 wheels was used to move Jumbo the 25 miles to Trinity Site.

As confidence in the plutonium bomb design grew, it was decided not to use Jumbo. Instead, it was placed under a steel tower about 800 yards from Ground Zero. The blast destroyed the tower, but Jumbo survived intact.

Today it rests at the entrance to ground zero so all can see it. The ends are missing because, in 1946, the Army placed eight 500-pound bombs inside it and detonated them.

Preparing the Gadget

To calibrate the instruments which would be measuring the atomic explosion and to practice a countdown, the Manhattan Project scientists ran a simulated blast on 7 May. They stacked 100 tons of TNT onto a 20-foot wooden platform just southeast of Ground Zero. Louis Hempelmann inserted a small amount of radioactive material from the Hanford, Washington facility into tubes running through the stack of crates. The scientists hoped to get a feel for how the radiation might spread in the real test by analyzing this test. The explosion destroyed the platform, leaving a small crater with trace amounts of radiation in it.

On 12 July, the two hemispheres of plutonium were carried to the George McDonald Ranch House just two miles from Ground Zero. At the house, Brigadier General Thomas Farrell, deputy to Major General Leslie Groves, was asked to sign a receipt for the plutonium. Farrell later said, “I recall that I asked them if I was going to sign for it shouldn’t I take it and handle it. So I took this heavy ball in my hand and I felt it growing warm, I got a certain sense of its hidden power. It wasn’t a cold piece of metal, but it was really a piece of metal that seemed to be working inside. Then maybe for the first time I began to believe some of the fantastic tales the scientists had told about this nuclear power.”

At the McDonald Ranch House, the master bedroom had been turned into a clean room for the assembly of the bomb core. According to Robert Bacher, a member of the assembly team, they tried to use only tools and materials from a special kit. Several of these kits existed and some were already on their way to Tinian by different routes. The idea was to test the procedures and tools at Trinity in addition to the bomb itself.

At one minute past midnight on Friday, 13 July, the explosives assembly left Los Alamos for Trinity Site. Later in the morning, assembly of the plutonium core began. According to Raemer Schreiber, Robert Bacher was the advisor, Marshall Holloway and Philip Morrison had overall responsibility. Louis Slotin, Boyce McDaniel, and Cyril Smith were responsible for the mechanical assembly in the ranch house. Later, Holloway was responsible for the mechanical assembly at the tower.

In the afternoon of the 13th, the core was taken to Ground Zero for insertion into the bomb mechanism. The bomb was assembled under the tower on 13 July. The plutonium core was inserted into the device with some difficulty. On the first try it stuck. After letting the temperatures of the plutonium and casing equalize, the core slid smoothly into place. Once the assembly was complete, many of the men went swimming in the water tank east of the McDonald Ranch House.

The next morning, the entire bomb was raised to the top of the 100-foot steel tower and placed in a small shelter. A crew then attached all the detonators and the Gadget was complete by 5:00pm.

Observation Points

Three observation points were established at 10,000 yards from Ground Zero. These were wooden shelters protected by concrete and earth. The south bunker served as the control center for the test. The automatic firing device was triggered from there as key men such as Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, head of Los Alamos, watched. None of the manned bunkers are left.

Many scientists and support personnel, including Major General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, watched the explosion from Base Camp, which was ten miles southwest of Ground Zero. All the buildings at Base Camp were removed after the test. Most visiting VIPs watched from Compania Hill, 20 miles northwest of Ground Zero.

The Day of the Trinity Test

The test was scheduled for 4:00am on 16 July, but rain and lightning early that morning caused it to be postponed. The device could not be exploded under rainy conditions because rain and winds would increase the danger from radioactive fallout and interfere with observation of the test. At 4:45am, the crucial weather report came through announcing calm to light winds with broken clouds for the following two hours.

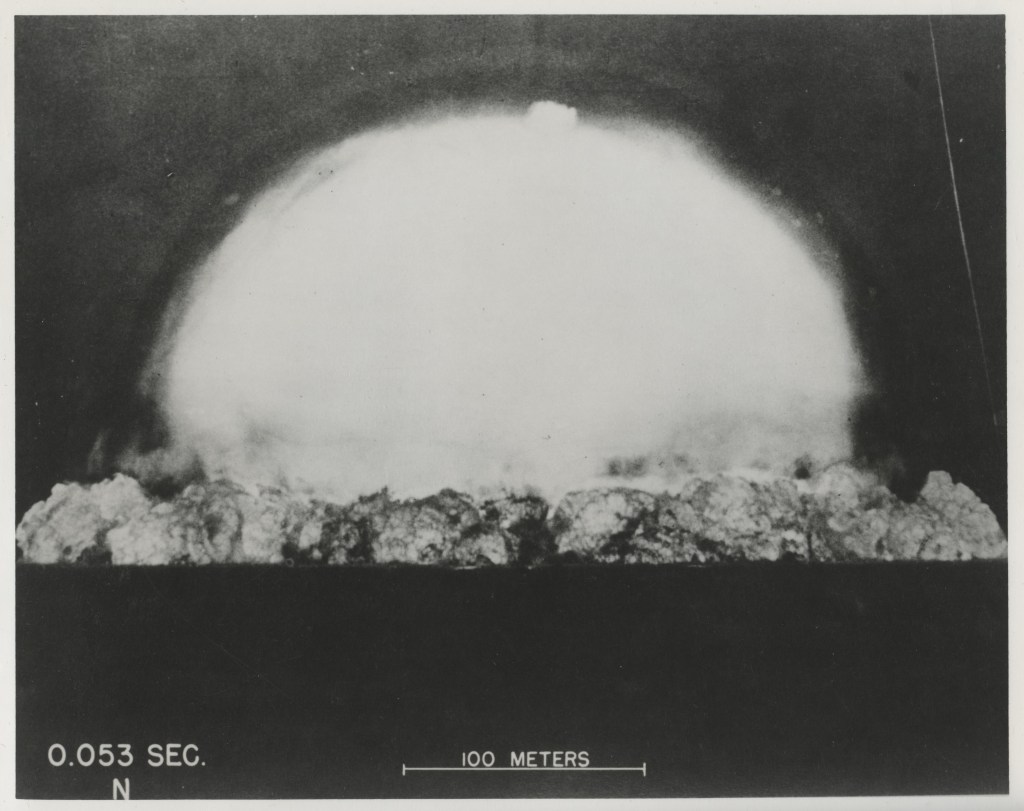

At 5:10am, the countdown started. At 5:29:45am, the Gadget exploded successfully. To most observers, the brilliance of the light from the explosion, watched through dark glasses, overshadowed the shock and sound wave that arrived later.

Hans Bethe, one of the contributing scientists, wrote that “it looked like a giant magnesium flare which kept on for what seemed a whole minute but was actually one or two seconds. The white ball grew and after a few seconds became clouded with dust whipped up by the explosion from the ground and rose and left behind a black trail of dust particles.”

Joe McKibben, another scientist, said, “We had a lot of flood lights on for taking movies of the control panel. When the bomb went off, the lights were drowned out by the big light coming in through the open door in the back.”

Others were impressed by the heat they immediately felt. Military policeman Davis said, “The heat was like opening up an oven door, even at 10 miles.” Dr. Phillip Morrison said, “Suddenly, not only was there a bright light but where we were, 10 miles away, there was the heat of the sun on our faces… Then, only minutes later, the real sun rose and again you felt the same heat to the face from the sunrise. So we saw two sunrises.”

Although no information on the test was released until after the atomic bomb was used as a weapon against Japan, people in New Mexico knew something had happened. The shock broke windows 120 miles away and was felt by many at least 160 miles away. Army officials simply stated that a munitions storage area had accidentally exploded at the Alamogordo Bombing Range.

The explosion did not make much of a crater. Most eyewitnesses describe the area as more of a small depression. The heat of the blast vaporized the steel tower and melted the desert sand and turned it into a green glassy substance. It was called Trinitite and can still be seen in the area. At one time, Trinitite completely covered the depression made by the explosion. Afterwards, the depression was filled in and much of the Trinitite was taken away by the Nuclear Energy Commission.

The story of what happened at Trinity Site did not come to light until after the second atomic bomb was exploded over Hiroshima, Japan on 6 August 1945. President Truman made the announcement that day. Three days later, 9 August, the third atomic bomb devastated the city of Nagasaki, and on 14 August, the Japanese surrendered.

Trinity Site became part of what was then White Sands Proving Ground. The Proving Ground was established on 9 July 1945 as a test facility to investigate the new rocket technology emerging from World War II. The land, including Trinity Site and the old Alamogordo Bombing Range, came under the control of the new rocket and missile testing facility.

In September 1945, press tours to the site started. One of the famous photos of Ground Zero shows Groves and Oppenheimer surrounded by a small group of reporters as they examine one of the footings to the 100-foot tower on which the bomb was placed. That picture was taken 11 September. At first, Trinity Site was encircled with a fence and radiation warning signs were posted. The site remained off limits to military and civilian personnel of the Proving Ground and closed to the public.

In 1952, the Atomic Energy Commission led a contract to clean up the site. Much of the Trinitite was scraped up and buried. In September 1953, about 650 people attended the first Trinity Site Open House. A few years later, a small group from Tularosa visited the site on the anniversary of the explosion to conduct a religious service and prayer for peace. In 1967, the inner oblong fence was added. In 1972, the corridor barbed wire fence which connects the outer fence to the inner one was completed. Jumbo was moved to the parking lot in 1979.