The Plutonium Implosion-Type Gadget

Of the three atomic bomb types, the uranium gun-type, plutonium gun-type, and plutonium implosion-type, considered by the Manhattan Project in World War II, only two of them, the uranium gun-type and plutonium implosion-type, were determined to be feasible. Of these two, only one, the plutonium implosion-type, would be tested prior to its use in combat. While extensive testing is typical for military equipment development, there were several factors that precluded even a minimally sufficient amount of testing outside of the laboratory.

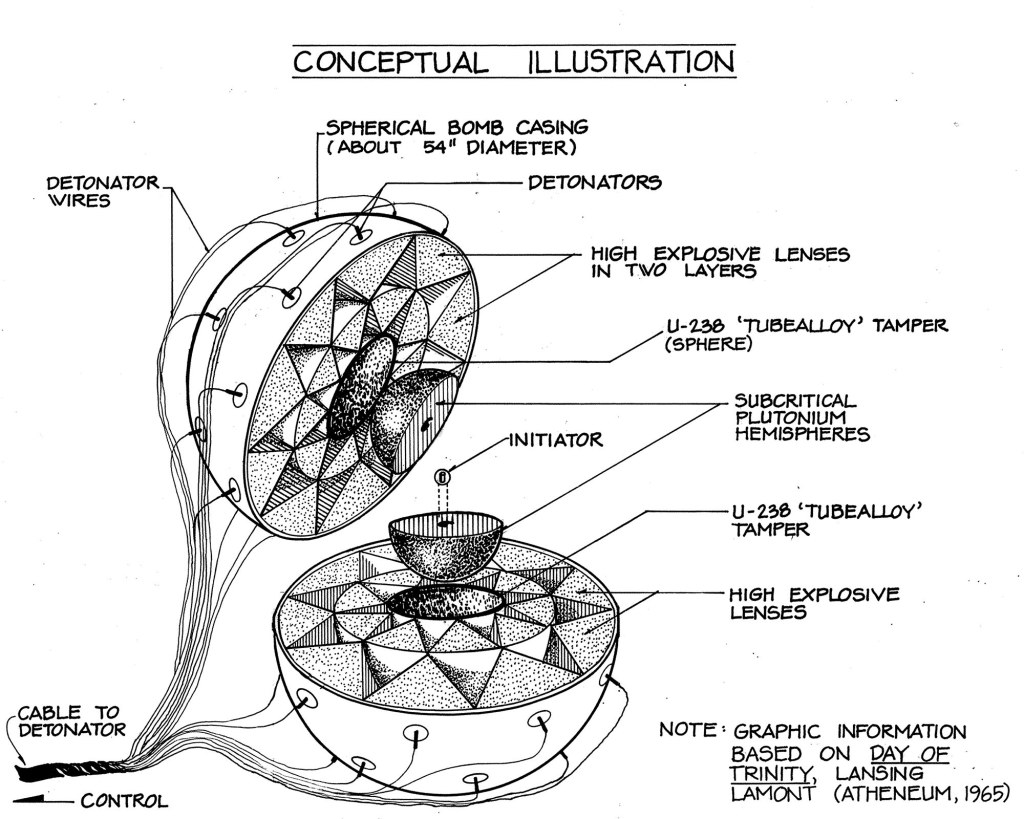

Both Fat Man and the Gadget were Y-1561 models and contained a plutonium core weighing 13.6 pounds (6.19 kilograms). Although designated as the same model, the two devices did have their differences. According to Robert F. Bacher, head of the “Gadget Division” (G-Division) at Los Alamos, Fat Man contained a ring that fit between the two hemispheres, intended to prevent pre-detonation due to a stream of neutrons running along the core’s seam. The Gadget tackled the same problem by covering the beryllium-polonium “urchin,” in nickel plating followed by a layer of gold foil. The urchin was located inside the plutonium core and was used to initiate nuclear fission by emanating a heavy shower of neutrons when compressed by the explosive lenses.

The Y-1561 models contained 32 detonators. Other models had different numbers of detonators, some were practice models, and others were prototypes. Model numbers changed as alterations were made throughout the course of the Manhattan Project and after World War II.

Although the enrichment sites at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington, were operational by the summer of 1945, uranium and plutonium enrichment had not yet reached intended production-level rates. When Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, less than 100 kilograms (220 pounds) of Uranium-235 had been produced at Oak Ridge and cast at Los Alamos. Because of its inefficient rate of fission, a single Little Boy-type weapon required 64 kilograms (141 pounds) of U-235. Manhattan Project planners had high confidence in the relatively simple gun-type device in the early stages of the project. The decision was made to forgo testing and proceed with preparations for dropping Little Boy on Japan while devoting a larger share of resources and manpower to the plutonium device.

While the physics and engineering for Little Boy were relatively straightforward, the same could not be said of the plutonium implosion-type bomb design. In order to compress the plutonium core into a critical mass, Manhattan Project engineers needed to find a way to create a completely symmetrical spherical implosion. The levels of precision needed were absolute and exact. If a single explosive lens was detonated too early or too late, the asymmetrical explosion would cause the pit to be blown out to one side of the bomb without being sufficiently compressed to sustain the reaction needed to convert enough mass into energy. This dreaded outcome was known as a “fizzle” and would mean that the device had failed or performed below the minimum acceptable yield of one kiloton.

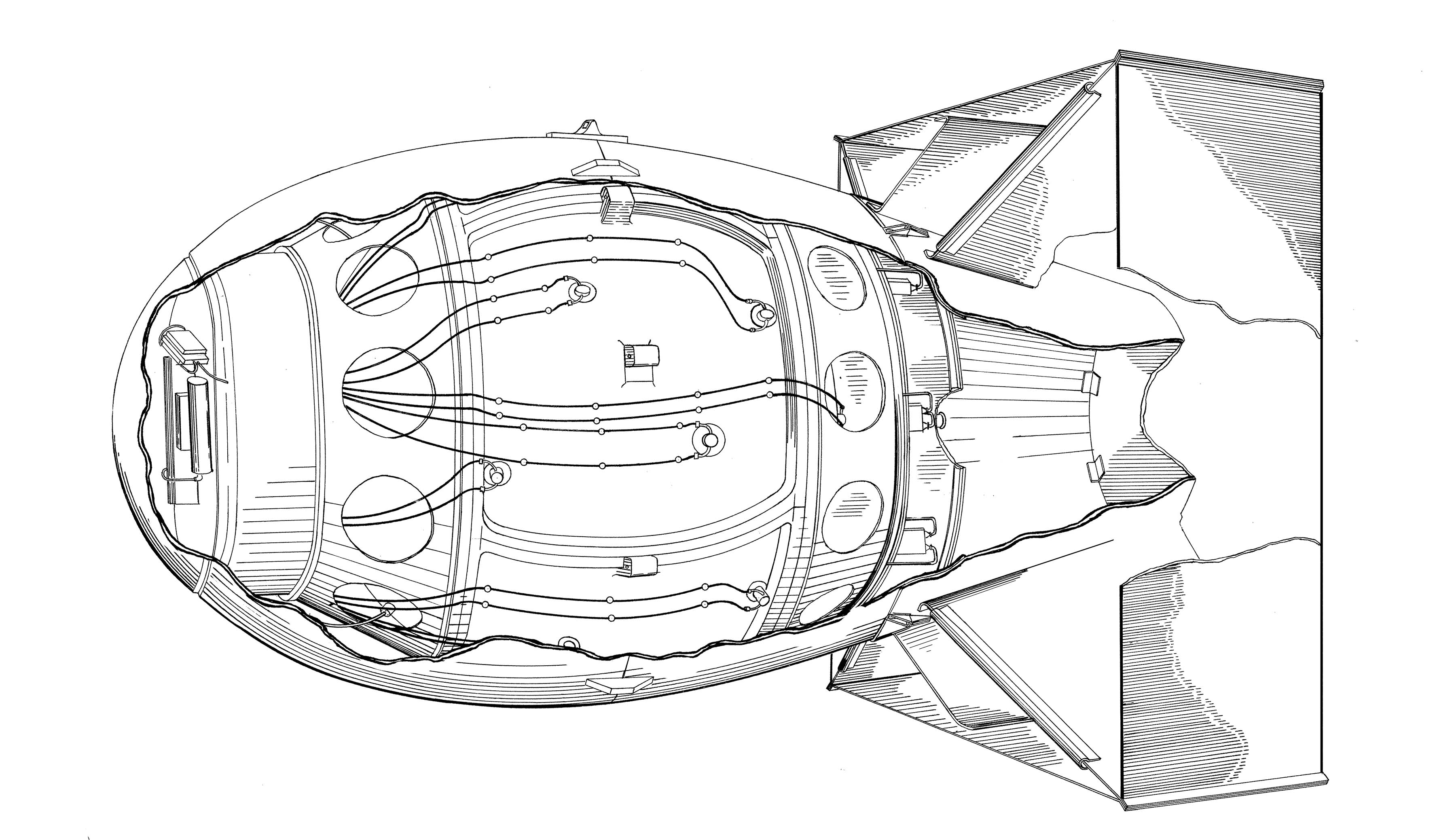

The Fat Man shell needed to be able to fully encapsulate the Gadget and still have room to allow for the peripheral systems, such as the firing set, radar equipment, and barometric units. Additionally, the entire unit had to be able to allow for the insertion and removal of safety and priming mechanisms. The result was a bulbous ellipsoidal figure with a box structure on the tail section.

The box-shaped tail section was actually to be used as the bomb’s parachute. Known as a California Parachute, the tail was designed to stabilize the bomb’s descent once dropped and then slow it down to allow enough time for the B-29 to bank away from the epicenter and the timer, radar antennae, and barometer to detonate the device at the appropriate moment and at the appropriate altitude. Both Fat Man and Little Boy utilized a California Parachute. However, later nuclear weapons would largely forego the bulky tail device. Engineering an aerodynamic shell to increase accuracy was not as much of a concern with the advent of thermonuclear weapons.

Plutonium Extraction and Handling

Uranium can be found naturally on Earth and occurs in sufficient enough concentrations and quantities to mine. The problem that faced the Manhattan Project physicists was that most uranium exists as U-238, an isotope that could not sustain a chain reaction in a way that resulted in an explosion. In order to build an atomic bomb, they would need to find a way to increase the amount of U-235, the fissile-ready uranium isotope. This process, known as enrichment, would demand the most time, energy, and money in the challenge to build a uranium atomic bomb. During World War II, the Allies were able to secure sources of uranium oxides, called uraninite or pitchblende, mined from sites in Colorado, the Eldorado and Echo Bay Mines in Canada, and at the Shinkolobwe Mine in the Belgian Congo.

As the largest naturally-occurring element in terms of atomic number, isotopes of uranium are inherently unstable and spontaneously undergo radioactive decay. One isotope, Uranium-235, is particularly suited for sustaining nuclear fission, in which neutrons colliding with a U-235 nucleus tend to break apart into smaller elements, such as barium and krypton, and emit neutrons as well as some energy. That energy increases exponentially with each generation of atoms undergoing fission. Adding that energy together and unleashing it in a fraction of a second results in an explosive yield that easily surpasses even the largest explosions caused by conventional means.

For a very rough example: of the 64 kilograms (141 pounds) of U-235 used in Little Boy, we will assume that 1.09 kilograms (2.4 pounds) actually underwent fission. As inefficient as Little Boy was, 1.09 kilograms of U-235 translates to approximately 2.793 x 1024 or 2,793,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms undergoing fission. Even with each of these two septillion seven hundred ninety-three sextillion atoms releasing only a tiny bit of energy (approximately 200 Mega-electron-Volts, or 200 MeV per uranium atom) and an overwhelmingly large amount of U-235 being wasted, Little Boy still resulted in a yield of approximately 16 kilotons (16,000 tons) of TNT.

Trans-uranium elements, those elements with atomic numbers greater than uranium (atomic number 92), are not found naturally on Earth. A few, including plutonium (atomic number 94), can occur naturally, but only in truly minuscule and transient (i.e. unusable) quantities. However, irradiating uranium in a pile or nuclear reactor could result in the creation of plutonium isotopes, albeit still in tiny quantities compared to the tons of uranium fed into the production reactors. When U-238 is bombarded in a reactor, it gains a neutron and becomes U-239. This isotope then decays into Neptunium-239, which again decays into Plutonium-239 relatively quickly.

After plutonium was first isolated and identified in early 1941 by a University of California, Berkeley team led by Glenn T. Seaborg, it was realized that plutonium isotopes could be a source of fissile material. Potentially, it could be an even better fissile material than U-235. And because the two elements are chemically different, it should be easier to separate the plutonium from the uranium when compared to the electromagnetic separation, gaseous diffusion, and liquid thermal diffusion processes of separating U-235 from U-238 being developed at the Clinton Engineering Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

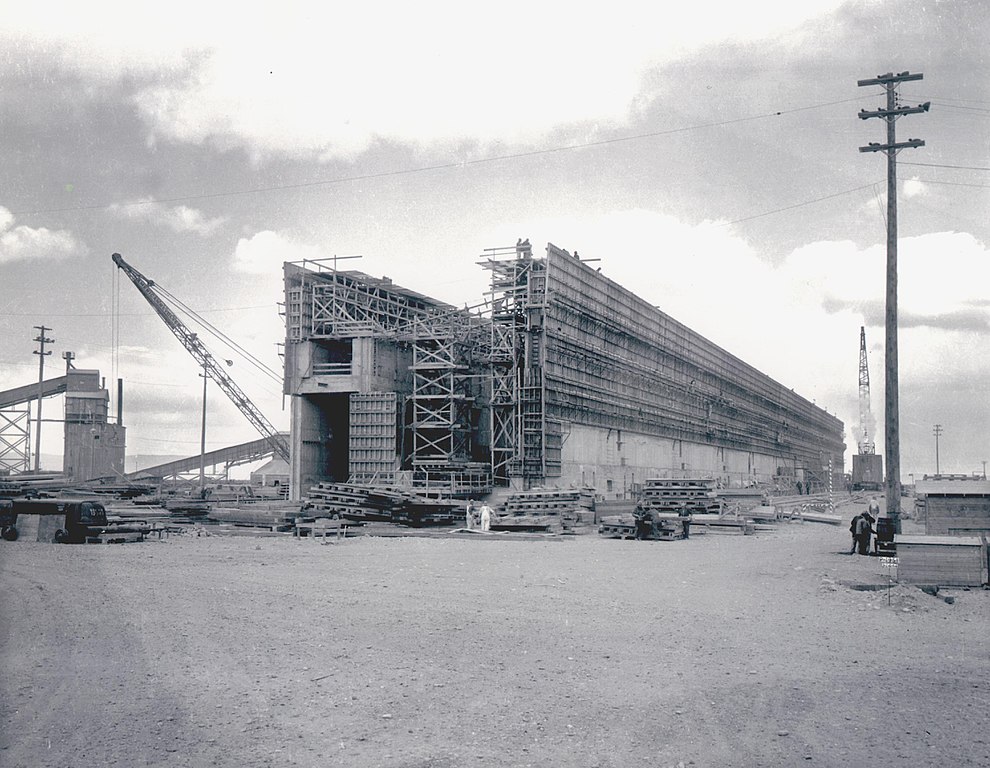

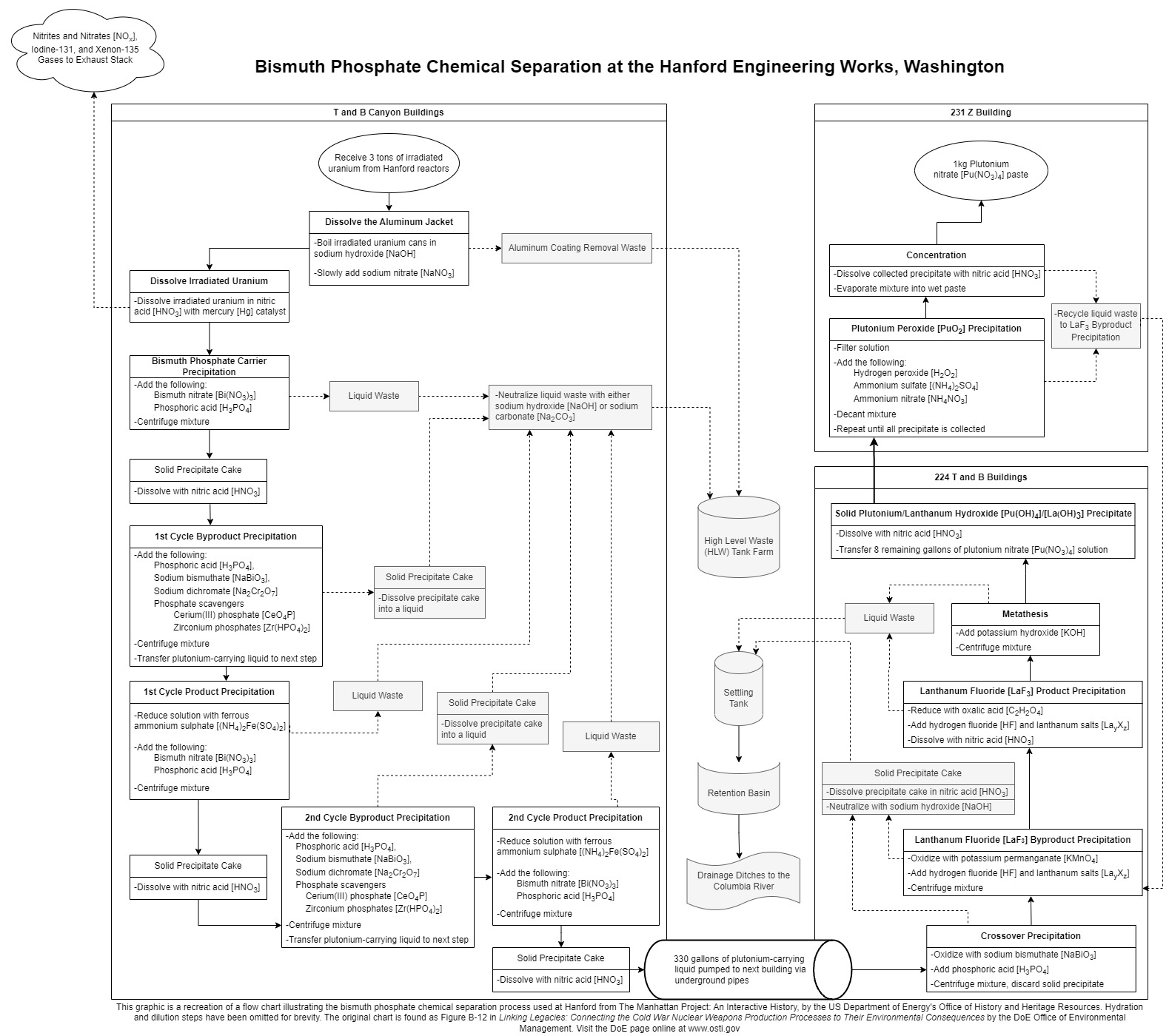

Even though chemical separation promised to be more efficient than isotope separation, the personnel at the Hanford, Washington site would still need to develop a way to process tons of uranium that would only result in tiny amounts of plutonium produced. From one metric ton of uranium, the separation plant would be able to extract around 0.5 pounds or 250 grams of Plutonium-239 by using the Bismuth-Phosphate Process to separate the plutonium and carry away unwanted impurities.

The first step in the process is to create the plutonium by irradiating uranium in a nuclear pile. To do this, uranium is machined into cylinders and then canned in an aluminum jacket, resulting in tubes called “slugs.” The slugs are then fed into each of the 2,004 holes designed in the nuclear pile’s lattice of graphite. As the slugs are bombarded with neutrons, some of the uranium is transmuted into plutonium, neptunium, and other radioactive elements. The vast majority of atoms and molecules in the slugs is still uranium. After the slugs are irradiated, technicians push fresh slugs into the pile, causing the irradiated slugs to be pushed out of the pile’s rear where they fall into a pool of water. The water allows the slugs to safely bleed off the radioactive products with relatively short half-lives.

Once the irradiated slugs have cooled down in both temperature and radioactivity, the slugs are moved to the Separation (200) Areas. Three tons of irradiated slugs enter the Canyon Buildings. Once the aluminum jackets are dissolved and discarded, the uranium slugs are dissolved in nitric acid. From here, they go through the Bismuth Phosphate Process in the Canyon Buildings, which reduces the three tons of uranium down to around 330 gallons (1,249 liters) of liquid solution and eliminates most of the radioactive elements. The liquid is then pumped into the 224 Buildings, where it undergoes another process using lanthanum fluoride and is further reduced down to eight gallons (thirty liters) of liquid solution.

After being transferred to the 231 Z Building, the last step involves concentrating the remaining plutonium. All that remains from the original three tons of slugs is around one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of plutonium nitrate in the form of a wet paste called “product,” which was packed into cans and prepared for shipment. Twenty cans were sent per shipment to Los Alamos for final processing into the plutonium metal that made up the bomb’s core. According to John Coster-Mullen, by the end of summer 1945, the Hanford plant had the capacity to produce one plutonium core every ten days.

The plutonium separation process was considered a “good enough” option for wartime production. After the war and after the dissolution of the Manhattan Engineering District, other processes were integrated and eventually replaced the Bismuth Phosphate Process. Unfortunately, the process produced a large volume of waste, most of which was either put into long-term storage tanks or drained into the Columbia River. Today, the areas around the 200-Area facilities are part of a superfund site managed by the Department of Energy, Environmental Protection Agency, and Washington state. Cleanup efforts began in 1989 and are focused on removing one billion cubic yards of solid and liquid High Level Waste that has contaminated the area.